|

| The Old Plantation, by John Rose, ca. 1785–1795.

The Hampton Folklore Society, founded in 1893 under the direction of the progressive educator Alice Bacon, was the first group of its kind composed mainly of African-American members. They published stories in the Southern Workman, the Hampton Institute’s journal; Gates and Tatar call this collaboration the first systematic collection of “black cultural artifacts.” Support from the anthropologist Franz Boas and American Folklore Society founder William Wells Newell, as well as works by writers like Zora Neale Hurston, Jean Toomer, Sterling A. Brown, Arthur Huff Fauset, Elsie Clews Parsons, and Edward C.L. Adams, sustained popular and academic interest throughout the years of the Harlem Renaissance.

Disagreements about the assimilation of folklore into the art of the modern “New Negro” caused one of the notable splits among Harlem intellectuals of the early 20th century. While some perceived traditional songs, stories, religious customs, and vernacular practices as crucial to intellectual emancipation from European lore (what Gates calls “structures of feeling, structures of thought”), others believed this assimilation would prolong enslavement to the past. One memorable debate unfolded in the pages of The Nation in 1926.

In “The Negro-Art Hokum,” writer George Schuyler (best known for his 1931 novel Black No More) argued that there was no such thing as a unitary black art, and that notions of a common artistic wellspring actually referred to the practices of the South’s black peasant class. Jazz and spirituals, for instance, were “no more expressive or characteristic of the Negro race than the music and dancing of the Appalachian highlanders…are expressive or characteristic of the Caucasian race.”

In a rebuttal, Langston Hughes, who would co-edit The Book of Negro Folklore with Arna Bontemps three decades later, argued that black artists must not go out of their way to avoid the source material of everyday life in black communities. A decades-long game of disavowal, on the one hand, and reclamation on the other foreshadowed the contemporary debates about black identity politics: Who are the “folk”? What issues should they care about? What stories should they preserve, disseminate, or kick to the curb?

Every tradition has its celebrities, and that’s certainly true of African-American folklore. There’s the tragic rail worker John Henry (Colson Whitehead’s 2001 novel John Henry Days centers on this story); the tar baby (see Toni Morrison’s 1981 novel Tar Baby); the desperado Stagolee (check out Cecil Brown’s 2006 fictionalization I, Stagolee). There are also lesser-known tales of a princess elephant, a yam that becomes a childless woman’s daughter, frogs that regurgitate finery for a ball, witches who slip out of their skins, magical tools, headless ghosts, stolen voices, singing tortoises, talking skulls, vindictive fairies, flying heifers, girls bewitched into nightingales, and warrior twins who journey to the land of Never Return and confront a menacing crocodile. Ballads recount the sinking of the Titanic, and we learn the dangers of fishing on Sundays and how wisdom first spread throughout the world.

Tatar, a scholar of German folklore, concedes that the “rage for order that takes hold of anthologizers vanishes in the face of the entangled histories and kaleidoscopic variations in stories from time past.” Drawing extensively on previously published anthologies, oral accounts, secondary literature, and university and governmental archives, the editors clearly envision their book not as a comprehensive collection but as an enticing introduction to an influential body of lore.

Their annotations clarify some slang and tropes, and the endnotes for certain stories offer useful background information and suggestive interpretations. (In a media moment that has largely focused on gains for black artists in television and film, the editors were recently honored as the recipients of an NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Literary Work.)

From The Nation Read More

|

Saturday, February 24, 2018

Natural Born Bards

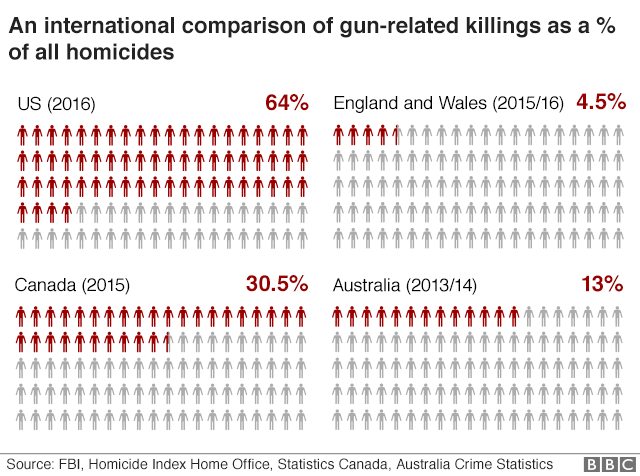

Guns – International Comparison of Killings

How does the US compare with other countries?

About 40% of Americans say they own a gun or live in a household with one, according to a 2017 survey, and the rate of murder or manslaughter by firearm is the highest in the developed world. There were more than 11,000 deaths as a result of murder or manslaughter involving a firearm in 2016.

Homicides are taken here to include murder and manslaughter. The FBI separates statistics for what it calls justifiable homicide, which includes the killing of a criminal by a police officer or private citizen in certain circumstances, which are not included.

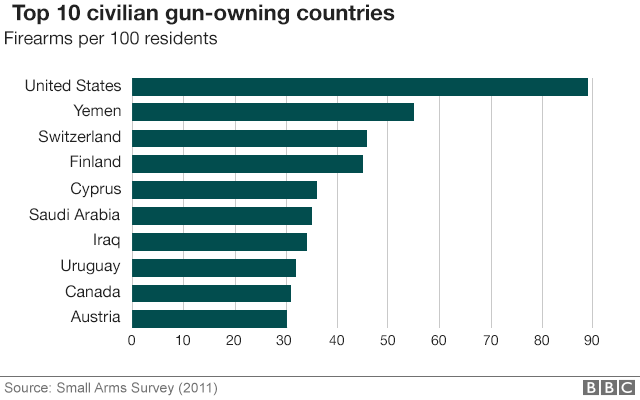

Who owns the world's guns?

While it is difficult to know exactly how many guns civilians own around the world, by every estimate the US with around 270 million is far out in front.

Switzerland and Finland are the European countries with the most guns per person - they both have compulsory military service for all men over the age of 18. Cyprus, Austria and Yemen also have military service.

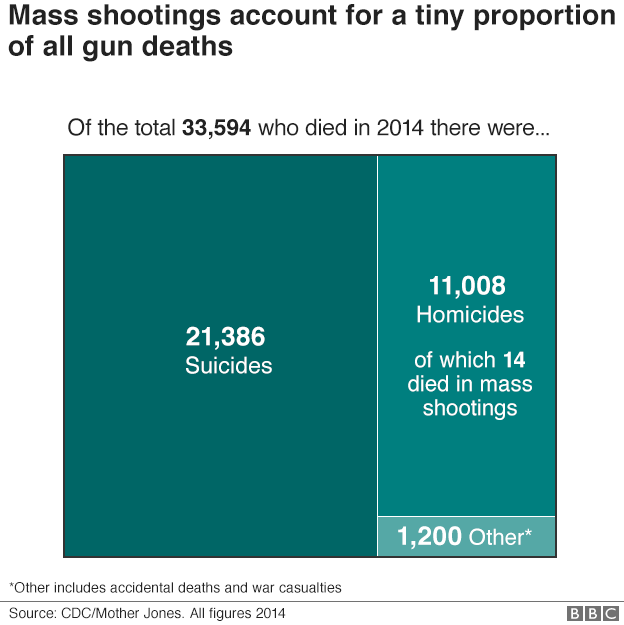

How do US gun deaths break down?

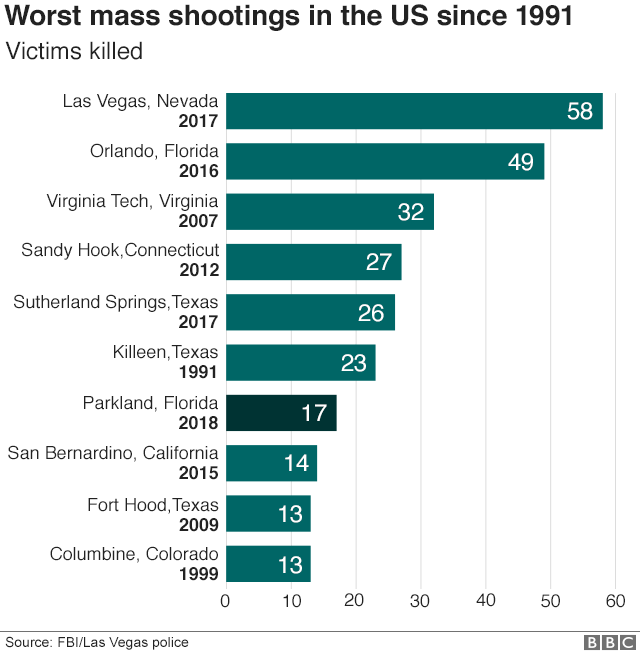

There have been more than 90 mass shootings in the US since 1982, according to investigative magazine Mother Jones.

Up until 2012, a mass shooting was defined as when an attacker had killed four or more victims in an indiscriminate rampage - and since 2013 the figures include attacks with three or more victims. The shootings do not include killings related to other crimes such as armed robbery or gang violence.

The overall number of people killed in mass shootings each year represents only a tiny percentage of the total number.

There were nearly twice as many suicides involving firearms in 2015 as there were murders involving guns, and the rate has been increasing in recent years. Suicide by firearm accounts for almost half of all suicides in the US, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A 2016 study published in the American Journal of Public Health found there was a strong relationship between higher levels of gun ownership in a state and higher firearm suicide rates for both men and women.

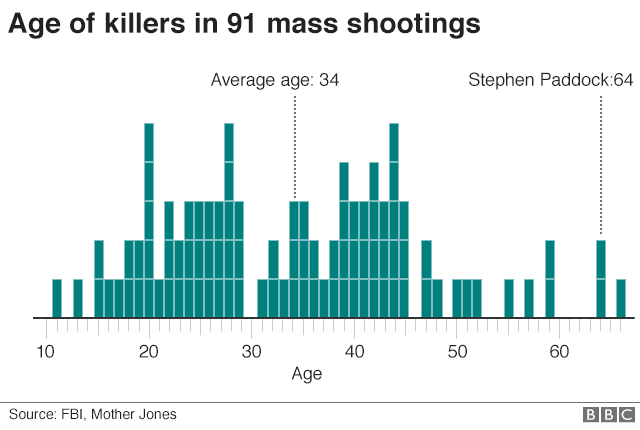

How old are the killers?

The average age of attackers in 91 recorded US mass shootings, including the Las Vegas attack, was 34.

Stephen Paddock, the gunman who killed 58 concertgoers in Las Vegas, is one of three killers aged over 60. The others are: William D Baker, 66, who killed five people in Illinois in 2001; and Kurt Myers, 64, who killed five people in New York state in 2013.

The youngest killer is Andrew Douglas Golden, 11, who ambushed students and teachers as they left Westside Middle School in Arkansas, in 1998. He was jointly responsible with Mitchell Scott Johnson, 13, for five deaths and 10 injured.

Attacks in US become deadlier

The Las Vegas attack was the worst in recent US history - and the three shootings with the highest number of casualties have all happened within the past 10 years.

The Parkland, Florida, attack is the worst school shooting since Sandy Hook in 2012.

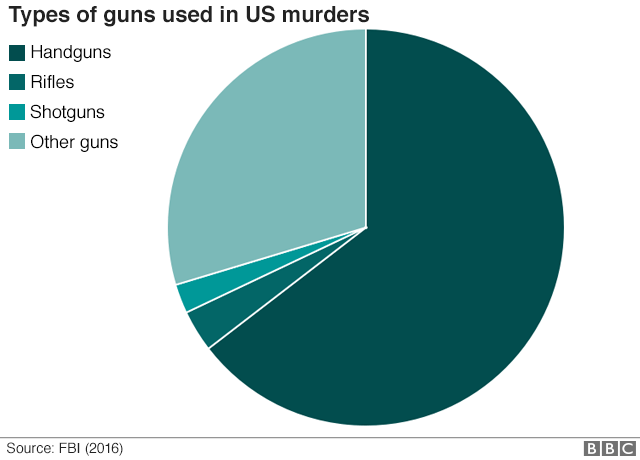

What types of guns kill Americans?

Military-style assault weapons have been blamed for some of the major mass shootings such as the attack in an Orlando nightclub and at the Sandy Hook School in Connecticut.

Dozens of rifles were recovered from the scene of the Las Vegas shooting, Police reported.

A few US states have banned assault weapons, which were totally restricted for a decade until 2004.

However most murders caused by guns involve handguns, according to FBI data.

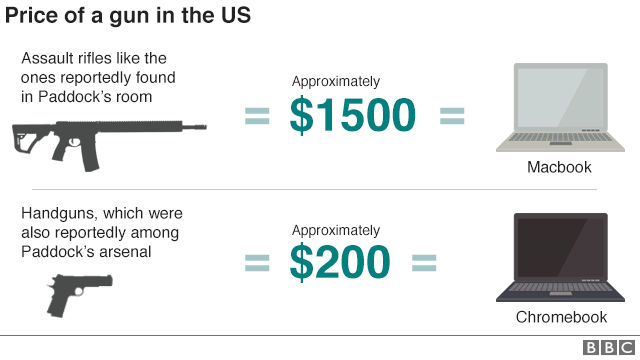

How much do guns cost to buy?

For those from countries where guns are not widely owned, it can be a surprise to discover that they are relatively cheap to purchase in the US.

Among the arsenal of weapons recovered from the hotel room of Las Vegas shooter Stephen Paddock were handguns, which can cost from as little $200 (£151) - comparable to a Chromebook laptop.

Assault rifles, also recovered from Paddock's room, can cost from around $1,500 (£1,132).

In addition to the 23 weapons at the hotel, a further 19 were recovered from Paddock's home. It is estimated that he may have spent more than $70,000 (£52,800) on firearms and accessories such as tripods, scopes, ammunition and cartridges.

Who supports gun control?

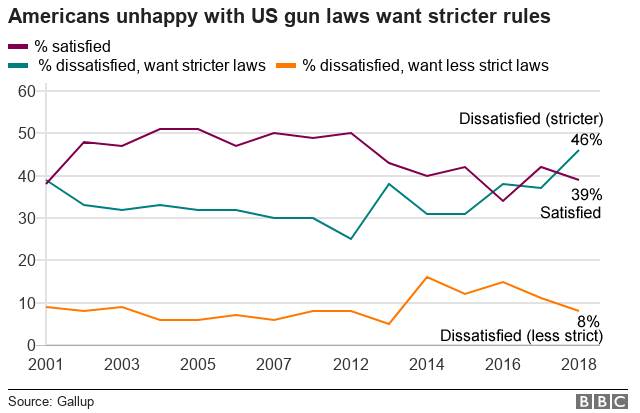

US public opinion on the banning of handguns has changed dramatically over the last 60 years. Support has shifted over time and now a significant majority opposes a ban on handguns, according to polling by Gallup.

But a majority of Americans say they are dissatisfied with US gun laws and policies, and most of those who are unhappy want stricter legislation.

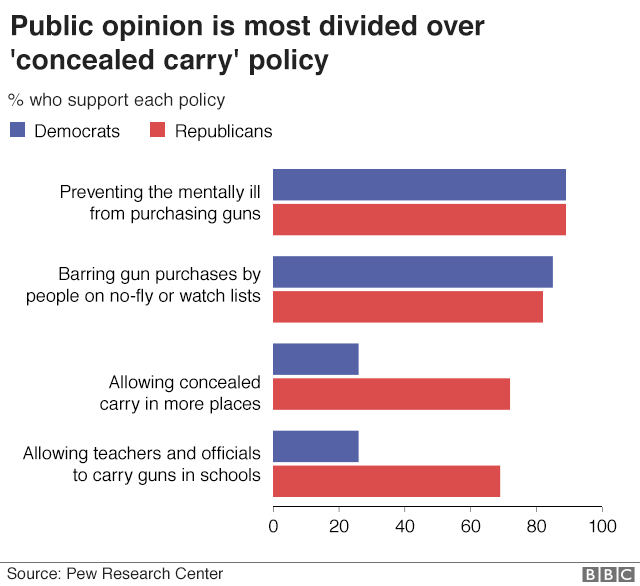

Some controls are widely supported by people across the political divide - such as restricting the sale of guns to people who are mentally ill, or on "watch" lists.

But Republicans and Democrats are much more divided over other policy proposals, such as whether to allow ordinary citizens increased rights to carry concealed weapons - according to a survey from Pew Research Center.

In his latest comment on the shootings, President Donald Trump said he would be "talking about gun laws as times goes by". The White House said now is not the time to be debating gun control.

His predecessor, Barack Obama, struggled to get any new gun control laws onto the statute books, because of Republican opposition.

Who opposes gun control?

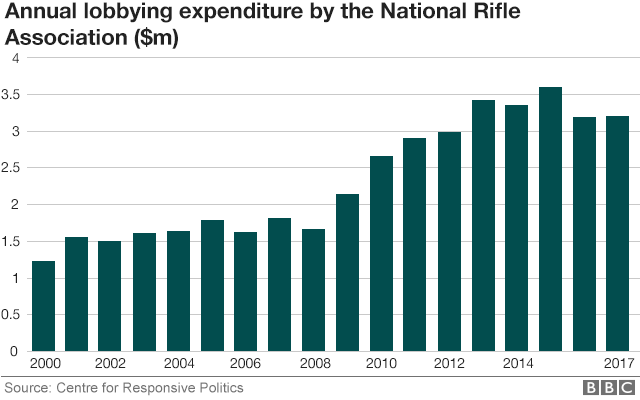

The National Rifle Association (NRA) campaigns against all forms of gun control in the US and argues that more guns make the country safer.

It is among the most powerful special interest lobby groups in the US, with a substantial budget to influence members of Congress on gun policy.

In total about one in five US gun owners say they are members of the NRA - and it has especially widespread support from Republican-leaning gun owners, according to Pew Research.

In terms of lobbying, the NRA officially spends about $3m per year to influence gun policy.

The chart shows only the recorded contributions to lawmakers published by the Senate Office of Public Records.

The NRA spends millions more elsewhere, such as on supporting the election campaigns of political candidates who oppose gun controls.

Friday, February 23, 2018

Zelda D'Aprano Fought for Equality All Her life !

Zelda D'Aprano fought for equality all her life. The fire in our bellies is her legacy

Leena van Deventer

As women, we have allowed ourselves to be the frogs in hot water. Zelda isn’t here any more to see us fix it, but fix it we will.

Zelda D’Aprano was an unstoppable force, and if you didn’t like it, you best got out of the way. It’s through my work as a director of the Victorian Women’s Trust that I got to know Zelda, and she has been a personal hero of mine ever since. I feel lucky for every conversation we had together. Each time I walked away feeling like I could do anything, and she utilised those powers very skilfully. She told me to ask for more from the world, even if I wanted the sun. So, to honour my friend: I’ll have your moon too, thanks.

Zelda D’Aprano passed away on Wednesday, at the age of 90. A staunch feminist, labour unionist, and pay justice advocate, Zelda had a profound and everlasting impact on the women’s movement and labour movements within Australia. She also took the time in her later years to mentor and nurture young feminists. I, and many others, are benefactors of that kindness, and we find ourselves grieving an immense loss.

She left school at 14 to join the workforce, and it was in this factory work she began to witness first-hand the inequity between male and female workers. With each job she took she would point out the injustice of this disparity to her employers and would be swiftly sacked. She didn’t care about personal consequences, she cared about fairness.

In 1969, fed up with the lack of progress for women, Zelda secured herself to the doors of the Commonwealth Building to protest the dismissal in the arbitration court of the equal pay case, of which she was a test case with the Australasian Meat Industry Employees Union (AMIEU). In an all-too-familiar pattern, for this “outspokenness” she was fired from the AMIEU.

Women weren’t allowed to drink in pubs, just in the ladies lounges, so she held pub crawls and invited all her friends. Women were only making 75c to the dollar, so she only paid 75% of her tram fare. I remember suggesting on one of my visits that she was the head of the “Ain’t Havin’ It Union” and she laughed.

The legislation Zelda fought for has been all but eroded. The Equal Pay Act of 1972 has been aggressively watered down to become the “Fair Work Act” and no longer even mentions “pay equity”, “gender discrimination” or “equal pay”. We allowed ourselves to be the frogs in the hot water. Zelda noticed, and I’m heartbroken she couldn’t stay long enough to see us fix it. But fix it we will.

When Zelda was chained to the doors of parliament, a police officer (foolishly underestimating her commitment) began to chastise her. “Aren’t you embarrassed? It’s just you on your own,” he said. Without hesitating, she replied “No. Because soon there will be three, then there will be five, and then there will be …”. She was right. Ten days after her protest she was joined by Alva Geikie and Thelma Solomon. From that action, the three women founded the Women’s Action Committee and the Women’s Liberation Centre, from which the Women’s Liberation Movement in Melbourne was born. This changed the landscape of feminist organising in Australia forever.

In her 1995 biography, Zelda described wanting to get more women involved in activism, because “we had passed the stage of caring about a “lady-like” image because women had for too long been polite ... and were still being ignored”. She didn’t care about what people thought of her, she cared about fairness.

The Women’s Action Committee organised the very first pro-choice rally in 1975, with an impressive turnout of over 500 women. It was reported by the media as a “hoard of angry barefoot women” taking to the streets. Zelda assured me they were definitely wearing shoes. She really did walk the walk, throughout her entire life.

As she outlived many of her friends and comrades, in her later years she described herself as lacking “good conversation” with fellow lefties and unionists. Someone from the Trades Hall’s women’s team would come every month to talk shop, and it was a highlight for everyone involved.

In 2015, the Victorian Trades Hall Council introduced the Zelda D’Aprano Award for union activism. In a bittersweet coincidence, the nominations for the 2018 award opened on the very day she passed away. The flag at Trades Hall was lowered to half mast in her honour.

The legacy of Zelda D’Aprano cannot be contained within memorial writings or obituaries, and it cannot die. It lives within the hearts of feminists – young and old – who, inspired by her spirit, will continue to fight for equality and fairness. It lives in the fire in our bellies. It lives in the smirk we wear when we are doubted. Even through the heartache of loss, it lives.

“Oh sisters, you’ve done me proud” – Zelda D’Aprano, 2015.

• Leena van Deventer is a writer, game developer and teacher from Melbourne

Leena van Deventer

|

| Zelda D’Aprano chained to the front doors of the Commonwealth Building in Melbourne in 1969. |

Zelda D’Aprano was an unstoppable force, and if you didn’t like it, you best got out of the way. It’s through my work as a director of the Victorian Women’s Trust that I got to know Zelda, and she has been a personal hero of mine ever since. I feel lucky for every conversation we had together. Each time I walked away feeling like I could do anything, and she utilised those powers very skilfully. She told me to ask for more from the world, even if I wanted the sun. So, to honour my friend: I’ll have your moon too, thanks.

Zelda D’Aprano passed away on Wednesday, at the age of 90. A staunch feminist, labour unionist, and pay justice advocate, Zelda had a profound and everlasting impact on the women’s movement and labour movements within Australia. She also took the time in her later years to mentor and nurture young feminists. I, and many others, are benefactors of that kindness, and we find ourselves grieving an immense loss.

She left school at 14 to join the workforce, and it was in this factory work she began to witness first-hand the inequity between male and female workers. With each job she took she would point out the injustice of this disparity to her employers and would be swiftly sacked. She didn’t care about personal consequences, she cared about fairness.

In 1969, fed up with the lack of progress for women, Zelda secured herself to the doors of the Commonwealth Building to protest the dismissal in the arbitration court of the equal pay case, of which she was a test case with the Australasian Meat Industry Employees Union (AMIEU). In an all-too-familiar pattern, for this “outspokenness” she was fired from the AMIEU.

Women weren’t allowed to drink in pubs, just in the ladies lounges, so she held pub crawls and invited all her friends. Women were only making 75c to the dollar, so she only paid 75% of her tram fare. I remember suggesting on one of my visits that she was the head of the “Ain’t Havin’ It Union” and she laughed.

The legislation Zelda fought for has been all but eroded. The Equal Pay Act of 1972 has been aggressively watered down to become the “Fair Work Act” and no longer even mentions “pay equity”, “gender discrimination” or “equal pay”. We allowed ourselves to be the frogs in the hot water. Zelda noticed, and I’m heartbroken she couldn’t stay long enough to see us fix it. But fix it we will.

When Zelda was chained to the doors of parliament, a police officer (foolishly underestimating her commitment) began to chastise her. “Aren’t you embarrassed? It’s just you on your own,” he said. Without hesitating, she replied “No. Because soon there will be three, then there will be five, and then there will be …”. She was right. Ten days after her protest she was joined by Alva Geikie and Thelma Solomon. From that action, the three women founded the Women’s Action Committee and the Women’s Liberation Centre, from which the Women’s Liberation Movement in Melbourne was born. This changed the landscape of feminist organising in Australia forever.

In her 1995 biography, Zelda described wanting to get more women involved in activism, because “we had passed the stage of caring about a “lady-like” image because women had for too long been polite ... and were still being ignored”. She didn’t care about what people thought of her, she cared about fairness.

The Women’s Action Committee organised the very first pro-choice rally in 1975, with an impressive turnout of over 500 women. It was reported by the media as a “hoard of angry barefoot women” taking to the streets. Zelda assured me they were definitely wearing shoes. She really did walk the walk, throughout her entire life.

As she outlived many of her friends and comrades, in her later years she described herself as lacking “good conversation” with fellow lefties and unionists. Someone from the Trades Hall’s women’s team would come every month to talk shop, and it was a highlight for everyone involved.

In 2015, the Victorian Trades Hall Council introduced the Zelda D’Aprano Award for union activism. In a bittersweet coincidence, the nominations for the 2018 award opened on the very day she passed away. The flag at Trades Hall was lowered to half mast in her honour.

The legacy of Zelda D’Aprano cannot be contained within memorial writings or obituaries, and it cannot die. It lives within the hearts of feminists – young and old – who, inspired by her spirit, will continue to fight for equality and fairness. It lives in the fire in our bellies. It lives in the smirk we wear when we are doubted. Even through the heartache of loss, it lives.

“Oh sisters, you’ve done me proud” – Zelda D’Aprano, 2015.

• Leena van Deventer is a writer, game developer and teacher from Melbourne

Wednesday, February 21, 2018

Friday, February 16, 2018

Grenfell Tower Billboards – “71 dead”, “And still no arrests?”

Grenfell Tower activists have parked three billboards opposite the remains of the charred north Kensington block, calling for justice on the eight-month anniversary of the fire.

Campaigners from Justice4Grenfell recreated a scene from Golden Globe-winning film “Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri” in a bid to raise awareness around the lack of arrests made in the investigation into the fire, which claimed 71 lives last June.

The posters, marked with “71 dead”, “And still no arrests?”, “How come?”, were driven through central London on Thursday before being parked in front of the remains of Grenfell Tower.

Campaign coordinator Yvette Williams said the group hoped the stunt would harness the power of advertising to bring about justice.

“We wanted to harness this power to remind people how little has been done since the tragic event shook this community, and the country, just over eight months ago,” she said.

“These billboards are here because there have still been no arrests, hundreds of survivors remain homeless, and 297 other towers in the UK are still covered in flammable cladding.

“Furthermore, requests from survivors of the Grenfell Tower fire to appoint a diverse decision-making panel to sit alongside the head of the public inquiry have been denied.”

Thursday, February 15, 2018

Sunday, February 11, 2018

The First Fleet arrives in Botany Bay, 21 January 1788

The First Fleet is the name given to the first group of eleven ships that carried convicts from England to Australia in 1788. Beginning in 1787 the ships departed with about 778 convicts (586 men, 192 women), provisions and agricultural implements. Seventeen convicts died and two were pardoned before departure. Another nine died before reaching Santa Cruz plus another 14 who died before arrival at Port Jackson, during the eight-month trip.

In 2005, the First Fleet Garden, a memorial to the First Fleet immigrants was created on the banks of Quirindi Creek at Wallabadah, New South Wales. Stonemason, Ray Collins, researched and then carved the names of all those who came out to Australia on the eleven ships in 1788 on tablets along the garden pathways. The stories of those who arrived on the ships, their life, and first encounters with the Australian country are presented throughout the garden.

No single definitive list of people who travelled on those ships exists; however, historians have pieced together as much data about these pioneers as possible. In the late 1980s, a simple software program with a database of convicts became available for Australian school students, both as a history and an information technology learning guide. An on-line version is now hosted by the University of Wollongong.

The six ships that transported the First Fleet convicts were:

Alexander

Charlotte

Friendship

Lady Penrhyn

Prince of Wales

Scarborough

Thursday, February 08, 2018

UK Centenary – UK Rights to Vote for Women

One hundred years ago, eight million British women secured the right to vote after a long struggle by the Suffragette movement.

It was not until a decade later that universal suffrage was introduced, but the 1918 Representation of the People Bill was still a major step forward that put the the country ahead of other nations, such as France.

Several countries, including former British colonies, outpaced the UK's rate of progress by introducing votes for women earlier.

New Zealand (1893)

The Pacific island nation, then a self-governing colony of the British Empire, was the first country to allow all women to vote in parliamentary elections. Women were not allowed to stand in the elections until 1919. New Zealand elected its first female Prime Minister Jenny Shipley in 1997.

Australia (1902)

The Australian Constitution extended voting rights to non-Aboriginal women across the country. Women in Southern and Western Australia had been able to vote in federal elections since the previous year. However, Aboriginal women and men were barred from voting in national elections until 1962.

Finland (1906)

The Nordic state, then part of Russia, blazed a trail for gender equality by becoming the first in the world to five women unrestricted rights to both vote and stand in parliamentary elections. Nineteen women became MPs in elections the next year.

Women demanding the right to vote in a march during the Russian Revolution

Norway (1913)

Middle-class women had won the right to vote in parliamentary elections in 1907. Six years later a motion to introduce universal suffrage was passed unanimously by MPs.

Denmark (1915)

Danish women won the right to vote in parliamentary elections following decades of increasingly disruptive campaigning. Suffrage was extended at the same time to women in Iceland, which was then part of the Kingdom of Denmark.

Russia (1917)

The government gave women the right to vote following months of suffragist rallies, including a 40,000-person march on the Tauride Palace.

|

| Suffragettes 1911 |

Several countries, including former British colonies, outpaced the UK's rate of progress by introducing votes for women earlier.

New Zealand (1893)

The Pacific island nation, then a self-governing colony of the British Empire, was the first country to allow all women to vote in parliamentary elections. Women were not allowed to stand in the elections until 1919. New Zealand elected its first female Prime Minister Jenny Shipley in 1997.

Australia (1902)

The Australian Constitution extended voting rights to non-Aboriginal women across the country. Women in Southern and Western Australia had been able to vote in federal elections since the previous year. However, Aboriginal women and men were barred from voting in national elections until 1962.

Finland (1906)

The Nordic state, then part of Russia, blazed a trail for gender equality by becoming the first in the world to five women unrestricted rights to both vote and stand in parliamentary elections. Nineteen women became MPs in elections the next year.

Women demanding the right to vote in a march during the Russian Revolution

Norway (1913)

Middle-class women had won the right to vote in parliamentary elections in 1907. Six years later a motion to introduce universal suffrage was passed unanimously by MPs.

Denmark (1915)

Danish women won the right to vote in parliamentary elections following decades of increasingly disruptive campaigning. Suffrage was extended at the same time to women in Iceland, which was then part of the Kingdom of Denmark.

|

| Wilhelmina Drucker (Dutch League for General Suffrage) with her portrait painted by Truus Claes in 1917 |

The government gave women the right to vote following months of suffragist rallies, including a 40,000-person march on the Tauride Palace.

Wednesday, February 07, 2018

Bakhtin Introduction

Krystyna Pomorska writes:

When Rabelais and His World, Mikhail Bakhtin's first book to be published in English, appeared in 1968, the author was totally unknown in the West. Moreover, his name, his biography, and his authorship were a mystery even in his native Russia. Today, Bakhtin (1895-1975) is internationally acclaimed in the world of letters and the humanities generally. His biography is gradually becoming better known as scholars from both East and West discover information and reconstruct the data.

His books, previously neglected or unknown, are being republished, such as the one introduced here. What accounts for the new popularity of this theoretician who wrote his pioneering works half a century ago and whose deep concern was a subject as "enigmatic" as literature? In response, we must look to his fundamental ideas about art, its ontology, and its context.

His roots in the intellectual life of the turn of the century, Bakhtin insisted that art is oriented toward communication. "Form" in art, thus conceived, is particularly active in expressing and conveying a system of values, a function that follows from the very nature of communication as an exchange of meaningful messages.

In such statements, Bakhtin recognizes the duality of every sign in art, where all content is formal and every form exists because of its content. In other words, "form" is active in any structure as a specific aspect of a "message." Even more striking are Bakhtin's ideas concerning the role of semiosis outside the domain of art, or, as he put it, in the organization of life itself. In opposition to interpretations of life as inert "chaos" that is transformed into organized "form" by art, Bakhtin claims that life itself (traditionally considered "content") is organized by human acts of behaviour and cognition and is therefore already charged with a system of values at the moment it enters into an artistic structure.

Art only transforms this organized "material" into a new system whose distinction is to mark new values. Bakhtin's semiotic orientation and his pioneering modernity of thought are grounded in his accounting for human behaviour as communication and, his recognition of the goal-directedness of all human messages. As a philosopher and literary scholar, Bakhtin had a "language obsession" as Michael Holquist calls it, or, as we might also say, a perfect understanding of language as a system; lie managed to use language comprehended as a model for his analysis of art, specifically the art of the novel.

As a philosopher and literary scholar, Bakhtin had a "language obsession" as Michael Holquist calls it, or, as we might also say, a perfect understanding of language as a system; lie managed to use language comprehended as a model for his analysis of art, specifically the art of the novel. Besides his revolutionary book on Dostoevsky, his essay "Discourse in the Novel" , written in 1934-35, belongs among the fundamental works on verbal art today. In it Bakhtin argues first and foremost against the outdated yet persistent idea of the "randomness" in the organization of the novel in contrast to poetry. He proved this assertion by demonstrating in his works the particular transformations of the comical in the epoch prior to the Renaissance parallels the rejection of "subcultures" in the years prior to the Second World War.

As Trubetzkoy showed in his unjustly neglected book, Europe and Mankind, this cultural "centrism" pertains not only to a social but also to an ethnic hierarchy. The danger of European cultural "centrism," the recognition of the multiplicity of cultural strata, their relative hierarchy, and their "dialogue" occupied Trubetzkoy all his life. The same is true of Bakhtin, as manifested in his works from the study on Dostoevsky (1929) to the Rabelais book (1965). This interest ties the author of Rabelais and His World to modern anthropology in America and in Europe.

Bakhtin's ideas concerning folk culture, with carnival as its indispensable component, are integral to his theory of art. The inherent features of carnival that he underscores are its emphatic and purposeful "heterglossia" and its multiplicity of styles. Thus, the carnival principle corresponds to and is indeed a part of the novelistic principle itself. One may say that just as dialogization is the sine qua non for the novel structure, so carnivalization is the condition for the ultimate "structure of life" that is formed by "behavior and cognition." Since the novel represents the very essence of life, it includes the carnivalesque in its properly transformed shape.

In his book on Dostoevsky, Bakhtin notes that "In carnival the new mode of man's relation to man is elaborated." One of the essential aspects of this relation is the "unmasking" and disclosing of the unvarnished truth under the veil of false claims and arbitrary ranks. Now, the role of dialogue—both historically and functionally, in language as a system as well as in the novel as a structure—is exactly the same. Bakhtin repeatedly points to the Socratian dialogue as a prototype of the discursive mechanism for revealing the truth.

Dialogue so conceived is opposed to the "authoritarian word" in the same way as carnival is opposed to official culture. The "authoritarian word" does not allow any other type of speech to approach and interfere with it. Devoid of any zones of cooperation with other types of words, the "authoritarian word" thus excludes dialogue. Similarly, any official culture that considers itself the only respectable model dismisses all other cul-tural strata as invalid or harmful.

Long before he published his book on Rabelais, Bakhtin had defined in the most exact terms the principle and the presence of the carnivalesque in his native literary heritage. However, the presence of carnival in Russian literature had been noted before Bakhtin, and a number of earlier critics and scholars had tried to approach and grasp this phenomenon. The nineteenth-century critic Vissarion Belinsky's renowned characterization of Gogol's universe as "laughter through tears" was probably the first observation of this kind.

The particular place and character of humour in Russian literature has been a subject of discussion ever since. Some scholars have claimed that humour, in the western sense, is precluded from Russian literature, with the exception of works by authors of non-Russian, especially southern, origin, such as Gogol, Mayakovsky, or Bulgakov. Some critics, notably Chizhevsky and, especially, Trubetzkoy, discussed the specific character of Dostoevsky's humour, and came close to perceiving its essence; yet they did not attain Bakhtin's depth and exactitude.

The official prohibition of certain kinds of laughter, irony, and satire was imposed upon the writers of Russia after the revolution. It is eloquent that in the 1930s Anatoly Lunacharsky, the Commissar of Enlightenment, himself wrote on the subject and organized a special government commission to study satiric genres.

The fate of Mayakovsky, Bulgakov, and Zoshchenko—the prominent continuers of the Gogolian and Dostoevskian tradition—testifies to the Soviet state's rejection of free satire and concern with national self irony, a situation similar to that prevailing during the Reformation. In defiance of this prohibition, both Rabelais and Bakhtin cultivated laughter, aware that laughter, like language, is uniquely characteristic of the human species.

|

| Mikhail Mikhailovich Bakhtin |

When Rabelais and His World, Mikhail Bakhtin's first book to be published in English, appeared in 1968, the author was totally unknown in the West. Moreover, his name, his biography, and his authorship were a mystery even in his native Russia. Today, Bakhtin (1895-1975) is internationally acclaimed in the world of letters and the humanities generally. His biography is gradually becoming better known as scholars from both East and West discover information and reconstruct the data.

His books, previously neglected or unknown, are being republished, such as the one introduced here. What accounts for the new popularity of this theoretician who wrote his pioneering works half a century ago and whose deep concern was a subject as "enigmatic" as literature? In response, we must look to his fundamental ideas about art, its ontology, and its context.

His roots in the intellectual life of the turn of the century, Bakhtin insisted that art is oriented toward communication. "Form" in art, thus conceived, is particularly active in expressing and conveying a system of values, a function that follows from the very nature of communication as an exchange of meaningful messages.

In such statements, Bakhtin recognizes the duality of every sign in art, where all content is formal and every form exists because of its content. In other words, "form" is active in any structure as a specific aspect of a "message." Even more striking are Bakhtin's ideas concerning the role of semiosis outside the domain of art, or, as he put it, in the organization of life itself. In opposition to interpretations of life as inert "chaos" that is transformed into organized "form" by art, Bakhtin claims that life itself (traditionally considered "content") is organized by human acts of behaviour and cognition and is therefore already charged with a system of values at the moment it enters into an artistic structure.

Art only transforms this organized "material" into a new system whose distinction is to mark new values. Bakhtin's semiotic orientation and his pioneering modernity of thought are grounded in his accounting for human behaviour as communication and, his recognition of the goal-directedness of all human messages. As a philosopher and literary scholar, Bakhtin had a "language obsession" as Michael Holquist calls it, or, as we might also say, a perfect understanding of language as a system; lie managed to use language comprehended as a model for his analysis of art, specifically the art of the novel.

As a philosopher and literary scholar, Bakhtin had a "language obsession" as Michael Holquist calls it, or, as we might also say, a perfect understanding of language as a system; lie managed to use language comprehended as a model for his analysis of art, specifically the art of the novel. Besides his revolutionary book on Dostoevsky, his essay "Discourse in the Novel" , written in 1934-35, belongs among the fundamental works on verbal art today. In it Bakhtin argues first and foremost against the outdated yet persistent idea of the "randomness" in the organization of the novel in contrast to poetry. He proved this assertion by demonstrating in his works the particular transformations of the comical in the epoch prior to the Renaissance parallels the rejection of "subcultures" in the years prior to the Second World War.

As Trubetzkoy showed in his unjustly neglected book, Europe and Mankind, this cultural "centrism" pertains not only to a social but also to an ethnic hierarchy. The danger of European cultural "centrism," the recognition of the multiplicity of cultural strata, their relative hierarchy, and their "dialogue" occupied Trubetzkoy all his life. The same is true of Bakhtin, as manifested in his works from the study on Dostoevsky (1929) to the Rabelais book (1965). This interest ties the author of Rabelais and His World to modern anthropology in America and in Europe.

Bakhtin's ideas concerning folk culture, with carnival as its indispensable component, are integral to his theory of art. The inherent features of carnival that he underscores are its emphatic and purposeful "heterglossia" and its multiplicity of styles. Thus, the carnival principle corresponds to and is indeed a part of the novelistic principle itself. One may say that just as dialogization is the sine qua non for the novel structure, so carnivalization is the condition for the ultimate "structure of life" that is formed by "behavior and cognition." Since the novel represents the very essence of life, it includes the carnivalesque in its properly transformed shape.

In his book on Dostoevsky, Bakhtin notes that "In carnival the new mode of man's relation to man is elaborated." One of the essential aspects of this relation is the "unmasking" and disclosing of the unvarnished truth under the veil of false claims and arbitrary ranks. Now, the role of dialogue—both historically and functionally, in language as a system as well as in the novel as a structure—is exactly the same. Bakhtin repeatedly points to the Socratian dialogue as a prototype of the discursive mechanism for revealing the truth.

Dialogue so conceived is opposed to the "authoritarian word" in the same way as carnival is opposed to official culture. The "authoritarian word" does not allow any other type of speech to approach and interfere with it. Devoid of any zones of cooperation with other types of words, the "authoritarian word" thus excludes dialogue. Similarly, any official culture that considers itself the only respectable model dismisses all other cul-tural strata as invalid or harmful.

Long before he published his book on Rabelais, Bakhtin had defined in the most exact terms the principle and the presence of the carnivalesque in his native literary heritage. However, the presence of carnival in Russian literature had been noted before Bakhtin, and a number of earlier critics and scholars had tried to approach and grasp this phenomenon. The nineteenth-century critic Vissarion Belinsky's renowned characterization of Gogol's universe as "laughter through tears" was probably the first observation of this kind.

The particular place and character of humour in Russian literature has been a subject of discussion ever since. Some scholars have claimed that humour, in the western sense, is precluded from Russian literature, with the exception of works by authors of non-Russian, especially southern, origin, such as Gogol, Mayakovsky, or Bulgakov. Some critics, notably Chizhevsky and, especially, Trubetzkoy, discussed the specific character of Dostoevsky's humour, and came close to perceiving its essence; yet they did not attain Bakhtin's depth and exactitude.

The official prohibition of certain kinds of laughter, irony, and satire was imposed upon the writers of Russia after the revolution. It is eloquent that in the 1930s Anatoly Lunacharsky, the Commissar of Enlightenment, himself wrote on the subject and organized a special government commission to study satiric genres.

The fate of Mayakovsky, Bulgakov, and Zoshchenko—the prominent continuers of the Gogolian and Dostoevskian tradition—testifies to the Soviet state's rejection of free satire and concern with national self irony, a situation similar to that prevailing during the Reformation. In defiance of this prohibition, both Rabelais and Bakhtin cultivated laughter, aware that laughter, like language, is uniquely characteristic of the human species.

Tuesday, February 06, 2018

Monday, February 05, 2018

Victor Kiernan (1913-2009)

V.G. Kiernan examined the manner in which the wars were conducted and their impact not only on the conquered societies but also on the societies which launched them. Kiernan addresses the ideology of empire - the concept of the civilizing mission, the triumph of civilization over barbarism - that the missionary organizations ardently supported. In reality, material profit was the prime motive, and he argues that colonialists and their propagandists did much to work up the nationalist rivalries and hatred which exploded in World War I.

Interweaving brilliant sketches of imperial and colonial life with analysis of the changing balance of economic and political power, Kiernan concludes by describing how the colonial liberation movements turned the tables in the aftermath of World War II.

Victor Gordon Kiernan ranks among Britain's most distinguished historians. After a fellowship at Trinity College, Cambridge, and a long period spent teaching in India, he joined the History Department at the University of Edinburgh, where he served as professor of modern history from 1970 until his retirement. Over the course of his life he authored such works as The Lords of Human Kind; America: From White Settlement to World Hegemony; Shakespeare: Poet and Citizen and numerous others, as well as translating two volumes of Urdu poetry.

To mark his 90th birthday, the future general secretary of the Communist party (Marxist) of India edited Across Time and Continents, a selection of Victor's writings and reminiscences of the subcontinent which had been closer to his heart than any other part of the 20th-century world.

Interweaving brilliant sketches of imperial and colonial life with analysis of the changing balance of economic and political power, Kiernan concludes by describing how the colonial liberation movements turned the tables in the aftermath of World War II.

Victor Gordon Kiernan ranks among Britain's most distinguished historians. After a fellowship at Trinity College, Cambridge, and a long period spent teaching in India, he joined the History Department at the University of Edinburgh, where he served as professor of modern history from 1970 until his retirement. Over the course of his life he authored such works as The Lords of Human Kind; America: From White Settlement to World Hegemony; Shakespeare: Poet and Citizen and numerous others, as well as translating two volumes of Urdu poetry.

To mark his 90th birthday, the future general secretary of the Communist party (Marxist) of India edited Across Time and Continents, a selection of Victor's writings and reminiscences of the subcontinent which had been closer to his heart than any other part of the 20th-century world.

Sunday, February 04, 2018

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)