Tuesday, June 30, 2020

Workers World "Ho Chi Minh: On Lynching & the Ku Klux Klan

Vietnam’s Ho Chi Minh: ‘On lynching & the Ku Klux Klan’

By a guest author posted on May 14, 2015

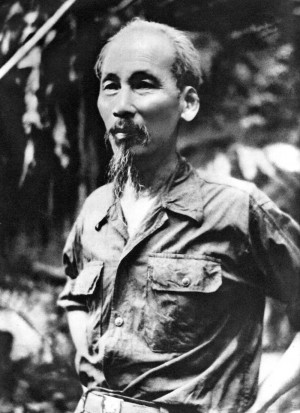

This May 19 will mark the 125th birthday anniversary of the great anti-imperialist leader, Ho Chi Minh. “Uncle Ho” was a leader of the National Liberation Front, a people’s army that defeated both French and U.S. military invaders in Vietnam. In honor of this legendary figure and the current Black Lives Matter uprising, WW is printing the following excerpts from a report made by this Vietnamese communist at the Fifth Congress of the Communist International gathering held in July 1924 in Moscow during the “National and Colonial Question” session. He died in 1969, six years before Vietnam’s liberation from U.S. imperialism. Go to tinyurl.com/n5nlck6 to read the entire report.

It is well-known that the Black race is the most oppressed and the most exploited of the human family. It is well-known that the spread of capitalism and the discovery of the New World had as an immediate result the rebirth of slavery. What everyone does not perhaps know is that after sixty-five years of so-called emancipation, American Negroes still endure atrocious moral and material sufferings, of which the most cruel and horrible is the custom of lynching.

[Charles] Lynch was the name of a planter in Virginia, a landlord and judge. Availing himself of the troubles of the War of Independence, he took the control of the whole district into his hands. He inflicted the most savage punishment, without trial or process of law, on Loyalists and Tories. Thanks to the slave traders, the Ku Klux Klan and other secret societies, the illegal and barbarous practice of lynching is spreading and continuing widely in the states of the American Union. It has become more inhuman since the emancipation of the Blacks, and is especially directed at the latter.

From 1899 to 1919, 2,600 Blacks were lynched, including 51 women and girls and ten former Great War soldiers.

Among 78 Blacks lynched in 1919, 11 were burned alive, three burned after having been killed, 31 shot, three tortured to death, one cut into pieces, one drowned and 11 put to death by various means.

Georgia heads the list with 22 victims. Mississippi follows with 12. Both have also three lynched soldiers to their credit.

Among the charges brought against the victims of 1919: one of having been a member of the League of Non-Partisans (independent farmers); one of having distributed revolutionary publications; one of expressing his opinion on lynchings too freely; one of having criticized the clashes between whites and Blacks in Chicago; one of having been known as a leader of the cause of the Blacks; and one for not getting out of the way and thus frightening a white child who was in a motorcar. In 1920, there were fifty lynchings, and in 1922 there were twenty-eight.

These crimes were all motivated by economic jealousy. Either the Negroes in the area were more prosperous than the whites, or the Black workers would not let themselves be exploited thoroughly. In all cases, the principal culprits were never troubled, for the simple reason that they were always incited, encouraged, spurred on and then protected by politicians, financiers and authorities, and above all, by the reactionary press.

The place of origin of the Ku Klux Klan is the southern United States. In May, 1866, after the Civil War, young people gathered together in a small locality of the state of Tennessee to set up a circle.

The victory of the federal government had just freed the Negroes and made them citizens. The agriculture of the South — deprived of its Black labor — was short of hands. Former landlords were exposed to ruin. The Klansmen proclaimed the principle of the supremacy of the white race. The agrarian and slaveholding bourgeoisie saw in the Klan a useful agent, almost a savior. They gave it all the help in their power. The Klan’s methods ranged from intimidation to murder.

The Negroes, having learned during the war that they are a force if united, are no longer allowing their kinsmen to be beaten or murdered with impunity. In July 1919, in Washington, they stood up to the Klan and a wild mob. The battle raged in the capital for four days. In August, they fought for five days against the Klan and the mob in Chicago. Seven regiments were mobilized to restore order. In September, the government was obliged to send federal troops to Omaha to put down similar strife. In various other states the Negroes defend themselves no less energetically.

Sunday, June 28, 2020

Useless Covid App hipe exposed

Despite 6 million downloads, the COVIDSafe app is yet to detect any unknown coronavirus contacts

It was sold as the key to unlocking restrictions – like sunscreen to protect Australians from Covid-19 but as the country begins to open up, the role of the Covidsafe app in the recovery seems to have dropped to marginal at best.

“This is an important protection for a Covid-safe Australia,” the prime minister, Scott Morrison, said in late April. “I would liken it to the fact that if you want to go outside when the sun is shining, you have got to put sunscreen on.”

“This is the same thing … If you want to return to a more liberated economy and society, it is important that we get increased numbers of downloads when it comes to the Covidsafe app … This is the ticket to ensuring that we can have eased restrictions.”

The health minister, Greg Hunt, tweeted that it was the key to being allowed to go back to watching football.

Vale George Parsons

It is with sadness that I share the email I received from our colleague, Associate Professor David Butt in the Department of Linguistics, and which I have been asked to share with you :

Over 4 decades, one of the wisest and most colourful of our scholars at Macquarie was the historian George Parsons (BA Hons MA Hons U.Syd. PhD Monash; and Hon Birkbeck College, London). Over the last weekend, George passed away in his sleep.

George was the learned and affable person one goes to campus to meet, and with whom discussions of the past, and on the economics and politics of the current moment, were always reasoned and enjoyable. He assisted staff at every level with advice (for which he was often sought out). He was noted also for his candid opposition, when it was deserved.

His network of intellectual contacts concerning Marxist History included one of the giants of C20th history, Eric Hobsbawm. They kept up exchanges even to recent years, and these exchanges illustrated the ideal of mentorship developing into scholarship, and friendship.

George died after months of home care by his partner, Dr. Margaret Hennessy, herself a scholar from Macquarie linguistics - a wonderful teacher, editor, and scholar of French language and culture.

George was an uncompromising scholar, a grand conversationalist, an energetic teacher, and a free spirit.

As many of you, I have had the opportunity for many conversations with George over the past decades and have always enjoyed his joviality and collegiality.

Best, Martina

Professor Martina Möllering

Executive Dean

Over 4 decades, one of the wisest and most colourful of our scholars at Macquarie was the historian George Parsons (BA Hons MA Hons U.Syd. PhD Monash; and Hon Birkbeck College, London). Over the last weekend, George passed away in his sleep.

George was the learned and affable person one goes to campus to meet, and with whom discussions of the past, and on the economics and politics of the current moment, were always reasoned and enjoyable. He assisted staff at every level with advice (for which he was often sought out). He was noted also for his candid opposition, when it was deserved.

His network of intellectual contacts concerning Marxist History included one of the giants of C20th history, Eric Hobsbawm. They kept up exchanges even to recent years, and these exchanges illustrated the ideal of mentorship developing into scholarship, and friendship.

George died after months of home care by his partner, Dr. Margaret Hennessy, herself a scholar from Macquarie linguistics - a wonderful teacher, editor, and scholar of French language and culture.

George was an uncompromising scholar, a grand conversationalist, an energetic teacher, and a free spirit.

As many of you, I have had the opportunity for many conversations with George over the past decades and have always enjoyed his joviality and collegiality.

Best, Martina

Professor Martina Möllering

Executive Dean

Permanent increase to JobSeeker and Youth Allowance must be enough to cover the basics

As reported today, the Government is considering a permanent increase to the old Newstart rate ($40 a day) of $10 a day, which would come into effect for people on JobSeeker, once the Coronavirus Supplement, which effectively doubled the old rate to $80 a day, is set to finish in September.

Australian Council of Social Service CEO Dr Cassandra Goldie said:

“We need to raise the rate of JobSeeker, Youth Allowance and other income support payments for good so that everyone has enough to cover the basics of life, like a roof over their head and food on the table.

“While we welcome that the Government is planning a permanent increase, it must allow people to cover the basics and we know that an increase of $10 a day won’t go far enough.

“We need to let people know we have their backs. We must adequately raise the rate of JobSeeker and Youth Allowance for good so that people can cover the basics they need to get by – a $10 a day increase to the old, low Newstart rate won’t be enough to allow people to cover their housing costs, food, bills and transport.

“As we handle the COVID-19 health crisis and confront the economic crisis, more people than ever before will struggle to find paid work. Just in the last week we’ve seen thousands of job losses.

“It’s clear to everyone, including the Government, that we can’t turn back to where we were when people were struggling to survive on $40 per day. This is not enough to live, let alone to cover the basics.

“There must be an adequate, permanent increase, which ensures people do not lose their homes. Even with the Supplement, only 1.5% of rentals are affordable for people on JobSeeker, Australia-wide. We know that with the Coronavirus Supplement people have been struggling to cover their rent. People are telling us they need every single dollar they are getting now with the doubling of JobSeeker in order to cover the essentials.

“Making sure people have enough to cover the basics is not only the right thing to do but the smart thing to do for the economy. A $75 per week permanent increase to the old rate is effectively a $200 per week cut to the current rate. Cutting the incomes of almost 2 million people by $200 per week in September would not be what businesses and the economy need to rebuild.

“To get through this crisis, we need to support each other, so everyone has access to the basics to rebuild their lives,” Dr Goldie said.

Media contact: Australian Council of Social Service, 0419 626 155

Australian Council of Social Service CEO Dr Cassandra Goldie said:

“We need to raise the rate of JobSeeker, Youth Allowance and other income support payments for good so that everyone has enough to cover the basics of life, like a roof over their head and food on the table.

“While we welcome that the Government is planning a permanent increase, it must allow people to cover the basics and we know that an increase of $10 a day won’t go far enough.

“We need to let people know we have their backs. We must adequately raise the rate of JobSeeker and Youth Allowance for good so that people can cover the basics they need to get by – a $10 a day increase to the old, low Newstart rate won’t be enough to allow people to cover their housing costs, food, bills and transport.

“As we handle the COVID-19 health crisis and confront the economic crisis, more people than ever before will struggle to find paid work. Just in the last week we’ve seen thousands of job losses.

“It’s clear to everyone, including the Government, that we can’t turn back to where we were when people were struggling to survive on $40 per day. This is not enough to live, let alone to cover the basics.

“There must be an adequate, permanent increase, which ensures people do not lose their homes. Even with the Supplement, only 1.5% of rentals are affordable for people on JobSeeker, Australia-wide. We know that with the Coronavirus Supplement people have been struggling to cover their rent. People are telling us they need every single dollar they are getting now with the doubling of JobSeeker in order to cover the essentials.

“Making sure people have enough to cover the basics is not only the right thing to do but the smart thing to do for the economy. A $75 per week permanent increase to the old rate is effectively a $200 per week cut to the current rate. Cutting the incomes of almost 2 million people by $200 per week in September would not be what businesses and the economy need to rebuild.

“To get through this crisis, we need to support each other, so everyone has access to the basics to rebuild their lives,” Dr Goldie said.

Media contact: Australian Council of Social Service, 0419 626 155

Friday, June 26, 2020

Ralph Samuel

The book is composed of a series of essays that were collected together to mark the ten year anniversary of Samuel's death in 1996. They describe the development of the British Communist Party in the 1940s and the experience of being a member of it from the vantage point of the 1980s.All of the three essays in the work were published by the New Left Review between 1984 and 1987.

The book engages with a number of different aspects of Communism in Britain, for example the way in which the party was organised on a top-down basis that was founded upon direction by the Comintern and that had elements of the Leninist idea of a 'vanguard party' centred on a small group of professional revolutionaries.

The book also examines the state of left-wing politics in the UK in the challenging environment of the Thatcherite 1980s and, in the case of the British Communist party of the time, the way in which it was divided between an 'old guard' faction and the younger forces aligned around Marxism Today at the time.[5] Samuel himself had left the organisation thirty years earlier. One of his overall assessments of the movement was that it embodied a "doomed, flawed but noble faith"

Raymond Williams

I come come from Pandy . . .” The first words spoken by Raymond Williams in Politics and Letters: Interviews with New Left Review (1979) may not have quite the rolling loquacity of the opening line of Saul Bellow’s Adventures of Augie March – “I am an American, Chicago born . . .” – but in their brisk way they bespeak a similar confidence.

Bellow’s narrator immediately situates his experience in the heart of America; Williams announced one of his main concerns in the title of his first novel, Border Country (1960). Borders – how they are constructed and recognised, how they impede and are crossed – are central to his thought. In contrast to March’s unequivocal belief (“I am an American”), Williams, whose work concentrated on the English literary and cultural tradition, came to identify himself as “a Welsh European”, emphasising what lay either side of a presumed centre, both locally and within an international context.

“It happened that in a predominantly urban and industrial Britain I was born in a remote village, in a very old settled countryside, on the border between England and Wales.” This is the account Williams gives of his origins in The Country and the City (1973), the simple facts of the matter beginning to unfurl and expand in the recognisable style of his analytical writing: an authority that draws power from a suggested hesitancy; the unhurried accumulation of material and argument; a continual elaboration and deepening of meaning. While Williams was proudly conscious of the convolutions of his own method and mode – “all my usual famous qualifying and complicating, my insistence on depths and ambiguities” – a former student, Terry Eagleton, remembers his lecturing style as that of “somebody who was talking in a human voice”.

Eagleton was struck also by the way that although Williams’s background might, by Cambridge standards, have been regarded as humble, it was also sufficiently “privileged” to give him “a sort of stability, a rootedness and self-assurance, and almost magisterial authority”. It gave him the confidence, while still an undergraduate – albeit an undergraduate who had served in the war – to stand up and insist, after a talk in which L C Knights claimed that a corrupt and mechanical civilisation could no longer understand neighbourliness, that he knew “perfectly well, from Wales, what neighbour meant”.

Confidence counts for little unless it is allied with determination. Combining this with an Orwellian sense “of the enormous injustice” of the world, Williams had the resources to develop his early critical and theoretical project – one that stressed the importance of shared experience and common meanings – in comparative isolation. In the process of becoming articulate in the language of a new and expansive kind of cultural history he also, in Raphael Samuel’s words, “constructed a conceptual vocabulary of his own”. The vocabulary was the cerebral expression of a temperament shaped by a particular geography and history. In Border Country Harry Price is “waiting for terms he could feel”. You could almost say he is waiting for the author to coin his most famous term, “structure of feeling”. Where Williams came from was inextricably linked with what he came to say.

Thursday, June 25, 2020

The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW : 1931 - 1954) Thu 26 Sep 1935 Page 11

Perhaps the most extraordinary South African incident resulted from an overnight jaunt, when he failed to arrive on the expected hour at a township where he was due to appear in the evening.

Ada Crossley and the rest of the party walked to the edge of the township anxiously scanning the surrounding veldt with binoculars.

Minutes passed and then quite unexpectedly a group of ferocious-looking Zulu warriors bounded over the horizon with Percy happily jogging along behind them. He wanted to invite his new friends to the concert, but had second thoughts when it was pointed out to him that such an action could have the entire party ignominiously drummed out of the country and possibly start another Boer War into the bargain.

Grainger in South Africa

John Bird p.88

Ada Crossley and the rest of the party walked to the edge of the township anxiously scanning the surrounding veldt with binoculars.

Minutes passed and then quite unexpectedly a group of ferocious-looking Zulu warriors bounded over the horizon with Percy happily jogging along behind them. He wanted to invite his new friends to the concert, but had second thoughts when it was pointed out to him that such an action could have the entire party ignominiously drummed out of the country and possibly start another Boer War into the bargain.

Grainger in South Africa

John Bird p.88

Professor John Blacking --- Grainger and the Complexity of Folk Music

Percy Grainger's emphasis on the complexity of folk music and the potential musicality of ordinary people, and his belief in the value of widely differing kinds of music have been upheld by the work of ethnomusicologists. Attempts to trace the evolution of the musical art from simple to complex, from one-tone to twelve-tone music and beyond, and to fit all the music of the world into such schemes, have proved fruitless.

Musical systems are derived neither from some universal emotional language nor from stages in the evolution of a musical art: they are made up of socially accepted patterns of sound that have been invented and developed by interacting individuals in the contexts of different social and cultural systems. If they have been diffused from one group to another, they have frequently been invested with new meanings and even new musical characteristics, because of the creative imagination of performers and listeners.

Role distinctions between creator, performer and listener, variations in musical styles and contrasts in the apparent musical ability of composers and performers, are consequences not of different genetic endowment, but of the division of labour in society, of the functional interrelationship of groups and of the commitment of individuals to music-making as a social activity.

Distinctions between music as 'folk', 'art', or 'popular' reflect a concern with musical products, rather than with the dynamic processes of music-making. Such distinctions tell us nothing substantive about different styles of music, and as categories of value they can be applied to all music.

'Popular' music as a general category of value, is music that is liked or admired by people in general, and it can include Bach, Beethoven, the Beatles, Ravi Shankar, Sousa's marches and the 'Londonderry Air' .

Far from being a patronising or derogatory term, it describes positively music that has succeeded in its basic aim to communicate as music. The music that most people value most is popular music; but what that music is varies according to the social class and experience of Composers, performers and listeners. Similarly, as Grainger Pointed out, 'folk' musicians strive for artistic perfection. As Eric Gill said, 'It isn't that artists are special kinds of people.'

Musical systems are derived neither from some universal emotional language nor from stages in the evolution of a musical art: they are made up of socially accepted patterns of sound that have been invented and developed by interacting individuals in the contexts of different social and cultural systems. If they have been diffused from one group to another, they have frequently been invested with new meanings and even new musical characteristics, because of the creative imagination of performers and listeners.

Role distinctions between creator, performer and listener, variations in musical styles and contrasts in the apparent musical ability of composers and performers, are consequences not of different genetic endowment, but of the division of labour in society, of the functional interrelationship of groups and of the commitment of individuals to music-making as a social activity.

Distinctions between music as 'folk', 'art', or 'popular' reflect a concern with musical products, rather than with the dynamic processes of music-making. Such distinctions tell us nothing substantive about different styles of music, and as categories of value they can be applied to all music.

'Popular' music as a general category of value, is music that is liked or admired by people in general, and it can include Bach, Beethoven, the Beatles, Ravi Shankar, Sousa's marches and the 'Londonderry Air' .

Far from being a patronising or derogatory term, it describes positively music that has succeeded in its basic aim to communicate as music. The music that most people value most is popular music; but what that music is varies according to the social class and experience of Composers, performers and listeners. Similarly, as Grainger Pointed out, 'folk' musicians strive for artistic perfection. As Eric Gill said, 'It isn't that artists are special kinds of people.'

The Australian Women's Weekly (1933 - 1982) Sat 5 Jan 1935 Page 14

Percy Grainger

ILLUSTRATING "tuneful percussions,"

a French version of a Java gong band

will be translated into the original Java-

nese during the course of a lecture-re-

cital by Percy Grainger to be broadcast

by all States on Sunday, January 6. The

composer, Debussy, was so much im-

pressed by the gong band engaged for

the recent Paris exhibition that he com-

posed "Pagodas" for it.

With a curious array of percussion in-

struments, Grainger proposes to show, in

effect, how Debussy sounds in the origi-

nal. The lowest notes of a grand piano

are to be struck by gong sticks to pro-

duce a soft percussion note, and oriental

effect will be enhanced by the celesta,

dulcetone, and marimba.

On Thursday, January 10, this notable

series of lecture-recitals will be closed

with illustrations of musical progress.

Percy Grainger proposes to give examples

of gliding tones, irregular rhythms, dis-

cordance harmony, intervals closer than

half tones, and "free" music of his own

composition.

—G.M.

ILLUSTRATING "tuneful percussions,"

a French version of a Java gong band

will be translated into the original Java-

nese during the course of a lecture-re-

cital by Percy Grainger to be broadcast

by all States on Sunday, January 6. The

composer, Debussy, was so much im-

pressed by the gong band engaged for

the recent Paris exhibition that he com-

posed "Pagodas" for it.

With a curious array of percussion in-

struments, Grainger proposes to show, in

effect, how Debussy sounds in the origi-

nal. The lowest notes of a grand piano

are to be struck by gong sticks to pro-

duce a soft percussion note, and oriental

effect will be enhanced by the celesta,

dulcetone, and marimba.

On Thursday, January 10, this notable

series of lecture-recitals will be closed

with illustrations of musical progress.

Percy Grainger proposes to give examples

of gliding tones, irregular rhythms, dis-

cordance harmony, intervals closer than

half tones, and "free" music of his own

composition.

—G.M.

Wednesday, June 24, 2020

Adolphe Sax

Percy Grainger was a great admirer of Jazz and the saxophone and when he joined the US Army in World War 1 was teaching the instrument to the delight of his students.

On October 25, 1932, Percy Grainger invited Duke Ellington and his orchestra to perform “Creole Love Call” as part of a music lecture at New York University. It was the first time any university had invited a jazz musician to perform in an academic context. That meeting of Grainger and Ellington is a prism refracting the broader story of the music academy’s slow and reluctant embrace of jazz. This story is, in turn, a cultural reflection of the broader African-American freedom struggle.

Duke Ellington, Percy Grainger, and the status of jazz in the music academy

On October 25, 1932, Percy Grainger invited Duke Ellington and his orchestra to perform “Creole Love Call” as part of a music lecture at New York University. It was the first time any university had invited a jazz musician to perform in an academic context. It has been argued that the meeting of Grainger and Ellington is a prism refracting the broader story of the music academy’s slow and reluctant embrace of jazz. This story is, in turn, a cultural reflection of the broader African-American freedom struggle.

Ellington had come to embody the cultural prestige now enjoyed by jazz. He appears on Washington DC’s state quarter, and his statue stands at the northeast corner of Central Park in New York City. In 1932, however, Ellington was known to official music culture only as the leader of a popular dance band and the writer of a few catchy tunes. Although he was already a celebrity, few white people outside of jazz fandom considered Ellington to be a serious artist.

That year, he received his first favorable review from a classical critic, followed by endorsements from Percy Grainger and a few other figures from the music establishment. This praise was unusual at the time. Most cultural authorities of that era held jazz in low regard, relegating it to the same position occupied by hip-hop today: undeniably popular, vibrant perhaps, but deficient in musical quality, and even, according to some critics, a threat to the nation’s morals.

Ellington’s ascent in stature parallels the social and political gains made by African-Americans in the twentieth century generally. Grainger’s role in the story is more complicated. He was prescient in his admiration for Ellington, and for jazz generally, but this admiration was coupled with condescension and lack of understanding.

Grainger was a an eccentric, and his ideas do not neatly map onto the music academy generally. Nevertheless, he is a useful reference point for the partial embrace that universities have made of jazz, and African-American diasporic music generally.

Duke Ellington

Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington was born on April 29, 1899. He grew up in a middle-class family in Washington, DC, which at the time had the nation’s largest urban black population (Tucker, 1990). His maternal grandfather had been born a slave, and his father was a butler in Warren Harding’s White House. Most middle-class black families at the time had a piano; the Ellington household had two.

Ellington attended the all-black Armstrong High School, whose principal, Carter G. Woodson, was a historian and the founder of The Journal of Negro Life and History. Woodson insisted that the curriculum put a strong emphasis on black history at all grade levels, and the school culture was one of black pride. Ellington studied harmony in high school and took private piano lessons, but he was not a dedicated student. He began performing in professional settings as a teenager, and by age 20, was leading his own band.

By 1932, Ellington had established himself as a major figure in jazz. He had released recordings of some of his most iconic compositions, including “East St Louis Toodle-oo” (1927), “Mood Indigo” (1930), and “Rockin’ in Rhythm” (1931). His performances at New York’s Cotton Club were broadcast nationally on NBC.

He had also been featured in one of the earliest musical short films, Black and Tan (1929). Sound in movies was still a technological novelty at the time, and RKO Radio Pictures produced Black and Tan to showcase their new Photophone system. It is worth examining this film in detail, because it so clearly illustrates the social position occupied by Ellington and his music at the time of its release.

On October 25, 1932, Percy Grainger invited Duke Ellington and his orchestra to perform “Creole Love Call” as part of a music lecture at New York University. It was the first time any university had invited a jazz musician to perform in an academic context. That meeting of Grainger and Ellington is a prism refracting the broader story of the music academy’s slow and reluctant embrace of jazz. This story is, in turn, a cultural reflection of the broader African-American freedom struggle.

The saxophone is only a few instruments in wide use today known to be invented by a single individual. His name is Adolphe Sax: Hence the name saxophone.

Adolphe Sax (1814 - 1894) was a musical instrument designer born in Belgium who could play many wind instruments. His idea was to create an instrument that combined the best qualities of a woodwind instrument with the best qualities of a brass instrument, and in the 1840s he conceived the saxophone. His invention was patented in Paris in 1846.

Duke Ellington, Percy Grainger, and the status of jazz in the music academy

On October 25, 1932, Percy Grainger invited Duke Ellington and his orchestra to perform “Creole Love Call” as part of a music lecture at New York University. It was the first time any university had invited a jazz musician to perform in an academic context. It has been argued that the meeting of Grainger and Ellington is a prism refracting the broader story of the music academy’s slow and reluctant embrace of jazz. This story is, in turn, a cultural reflection of the broader African-American freedom struggle.

Ellington had come to embody the cultural prestige now enjoyed by jazz. He appears on Washington DC’s state quarter, and his statue stands at the northeast corner of Central Park in New York City. In 1932, however, Ellington was known to official music culture only as the leader of a popular dance band and the writer of a few catchy tunes. Although he was already a celebrity, few white people outside of jazz fandom considered Ellington to be a serious artist.

That year, he received his first favorable review from a classical critic, followed by endorsements from Percy Grainger and a few other figures from the music establishment. This praise was unusual at the time. Most cultural authorities of that era held jazz in low regard, relegating it to the same position occupied by hip-hop today: undeniably popular, vibrant perhaps, but deficient in musical quality, and even, according to some critics, a threat to the nation’s morals.

Ellington’s ascent in stature parallels the social and political gains made by African-Americans in the twentieth century generally. Grainger’s role in the story is more complicated. He was prescient in his admiration for Ellington, and for jazz generally, but this admiration was coupled with condescension and lack of understanding.

Grainger was a an eccentric, and his ideas do not neatly map onto the music academy generally. Nevertheless, he is a useful reference point for the partial embrace that universities have made of jazz, and African-American diasporic music generally.

Duke Ellington

Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington was born on April 29, 1899. He grew up in a middle-class family in Washington, DC, which at the time had the nation’s largest urban black population (Tucker, 1990). His maternal grandfather had been born a slave, and his father was a butler in Warren Harding’s White House. Most middle-class black families at the time had a piano; the Ellington household had two.

Ellington attended the all-black Armstrong High School, whose principal, Carter G. Woodson, was a historian and the founder of The Journal of Negro Life and History. Woodson insisted that the curriculum put a strong emphasis on black history at all grade levels, and the school culture was one of black pride. Ellington studied harmony in high school and took private piano lessons, but he was not a dedicated student. He began performing in professional settings as a teenager, and by age 20, was leading his own band.

By 1932, Ellington had established himself as a major figure in jazz. He had released recordings of some of his most iconic compositions, including “East St Louis Toodle-oo” (1927), “Mood Indigo” (1930), and “Rockin’ in Rhythm” (1931). His performances at New York’s Cotton Club were broadcast nationally on NBC.

He had also been featured in one of the earliest musical short films, Black and Tan (1929). Sound in movies was still a technological novelty at the time, and RKO Radio Pictures produced Black and Tan to showcase their new Photophone system. It is worth examining this film in detail, because it so clearly illustrates the social position occupied by Ellington and his music at the time of its release.

Tuesday, June 23, 2020

Monday, June 22, 2020

Vast neolithic circle of deep shafts found near Stonehenge

Vast neolithic circle of deep shafts found near Stonehenge Exclusive: prehistoric structure spanning 1.2 miles in diameter is masterpiece of engineering, say archaeologists Dalya Alberge Published

15:00 Monday, 22 June 2020 Follow Dalya Alberge A circle of deep shafts has been discovered near the world heritage site of Stonehenge, to the astonishment of archaeologists, who have described it as the largest prehistoric structure ever found in Britain.

Four thousand five hundred years ago, the Neolithic peoples who constructed Stonehenge, a masterpiece of engineering, also dug a series of shafts aligned to form a circle spanning 1.2 miles (2km) in diameter. The structure appears to have been a boundary guiding people to a sacred area because Durrington Walls, one of Britain’s largest henge monuments, is located precisely at its centre. The site is 1.9 miles north-east of Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain, near Amesbury, Wiltshire. Prof Vincent Gaffney, a leading archaeologist on the project.

A circle of deep shafts has been discovered near the world heritage site of Stonehenge, to the astonishment of archaeologists, who have described it as the largest prehistoric structure ever found in Britain.

Four thousand five hundred years ago, the Neolithic peoples who constructed Stonehenge, a masterpiece of engineering, also dug a series of shafts aligned to form a circle spanning 1.2 miles (2km) in diameter. The structure appears to have been a boundary guiding people to a sacred area because Durrington Walls, one of Britain’s largest henge monuments, is located precisely at its centre. The site is 1.9 miles north-east of Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain, near Amesbury, Wiltshire.

Prof Vincent Gaffney, a leading archaeologist on the project, said: “This is an unprecedented find of major significance within the UK. Key researchers on Stonehenge and its landscape have been taken aback by the scale of the structure and the fact that it hadn’t been discovered until now so close to Stonehenge.”

Liberals have cut $2.2 billion from Australian universities, and increased university fees and student debt.

The Liberals have cut $2.2 billion from Australian universities, and increased university fees and student debt.

Labor believes access to university should be determined by your ability and willingness to work hard, not your bank balance. But every day Scott Morrison is putting universities more out of reach for students.

Will you sign our petition and join the campaign to stop the Liberals’ attack on universities?

Dr Herbert Vere Evatt (1894-1965)

Dr Herbert Vere Evatt (1894-1965) realised many of the labour movement's highest ideals, as a scholar, lawyer, High Court Judge, and the Attorney General and Minister for External Affairs (now Foreign Affairs) in the Curtin and Chifley governments, and as the Leader of the Opposition during the 1950s.

He was one of the great innovators of the labour movement, influencing Australian public policy and society to this day. His achievements and uncompromising stand for just principles in public life will always be remembered.

Dr Evatt initiated Australia's first independent foreign policy and became widely recognised around the world as a supporter of the right of the smaller nations to peaceful development and equality.

As leader of the Australian delegation to the meeting that founded the United Nations in San Francisco in 1945, he took the step of including a woman in the delegation. The woman was Jessie Street. This was a brave move for a political leader in those days, when women in politics were not highly regarded by most male politicians.

At the San Francisco Conference, Dr Evatt spoke to the Great Powers on behalf of the other nations of the world with a voice that commanded universal respect. After three months of diplomatic struggle, the Charter of the United Nations was adopted; a Charter that had become more humane and larger in scope, now containing provisions for the poor, the weak and the oppressed, provisions that had never been envisaged by the Great Powers. Alan Renouf characterised Evatt's performance as

"of virtuoso quality: for sheer brilliance in an international forum there is nothing in Australia's diplomatic annals to surpass it. For the public, he was one of the outstanding personalities (newspaper representatives voted Harold Stassen of the United States and Evatt as the most impressive delegates). Abroad, he was loaded with praise ...

The reputation Evatt won for himself as the voice of Australia long endured in the United Nations. It brought great credit to his country; more than any other national leader, Evatt made Australia known universally and made it known as a country of courage, responsibility and liberalism ... Deprived throughout the war of the say to which Evatt thought Australia was entitled, he had his reward at San Francisco, where Australia was heard as never before. What was of more lasting value was that when it was heard, it had something worthwhile to say."

In 1948 Dr Evatt was elected President of the General Assembly of the United Nations, the only Australian to have ever held the position. He presided over the adoption and proclamation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the cornerstone of human rights protection throughout the modern world. "It was the first occasion on which the organised community of nations had made a declaration of human rights and fundamental freedoms", Evatt reflected, "millions of people, men, women and children all over the world would turn to it for help, guidance and inspiration."

After Labor lost office in 1949, the Doc's fights for freedom continued. Against all odds, in 1950 he contested the Communist Party Dissolution Act introduced by the Menzies government in the High Court and won, saving Australia from a serious blot on its democracy.

Doc Evatt and his wife Mary Alice were also great patrons of the arts and gave encouragement to struggling young Australian artists, including Russell Drysdale and Sidney Nolan, purchasing many of their paintings and drawings and donating them to galleries and local councils around the country.

Faith Bandler, the leader of the 1967 referendum that formally recognised Indigenous Australians and one of Dr Evatt's greatest admirers, paid tribute in a speech to the inaugural meeting of the Foundation in 1979.

Becoming John Curtin and James Scullin

Join ACTU Secretary Sally McManus and ALP President Wayne Swan for this commemoration of John Curtin’s life and legacy as a union activist and wartime prime minister on the 75th anniversary of his death. We will also be launching the new biography of Curtin, Becoming John Curtin and James Scullin (Melbourne University Publishing 2020) by Liam Byrne.

5 July 2020, 6-7pm AEST. You can register for this special online event

Sunday, June 21, 2020

Saturday, June 20, 2020

Cecil Sharp House on Percy Grainger

Percy Aldridge Grainger (1882-1961)

Percy Grainger was born George Percy Grainger at Brighton, Victoria, Australia, on 8 July 1882, the son of John Harry Grainger (1855-1917), architect and engineer, and his wife, Rosa Annie (Rose) Aldridge (1861-1922). He spent his childhood in Melbourne, Victoria, where he was privately educated under the guidance of his musically gifted mother. He received supplementary lessons in languages, art, elocution and drama, and the piano. His early interest in classical legends and Icelandic sagas influenced him for the rest of his life.

By 1895, Grainger's obvious talent with the piano led him to pursue studies in Germany. At the Hoch Conservatorium he socialised with several older British students and fell under the spell of Rudyard Kipling, settings of whose verses he worked on between 1898 and 1956. From 1901 to 1914, he made a living as a concert pianist and private teacher in London, undertaking frequent tours of northern Europe and two lengthy Antipodean visits. During the first half of his residence in London, when often fulfilling subsidiary musical roles, Grainger also depended upon sponsorship by such leading musicians as Sir Charles Villiers Stanford and Sir Henry Wood. In 1911 he changed his name to Percy Aldridge Grainger.

Like much of the English musical establishment of this period, Grainger became fascinated with folk song and set out to collect songs and tunes, initially in Lincolnshire, in 1905. Unlike most of his contemporaries, Grainger became an enthusiastic supporter of the Edison Phonograph as a means of collecting and began using it at Brigg - a small market town in North Lincolnshire, England - the following year, recording the now legendary Joseph Taylor, whom he brought to London to record songs for the Gramophone Company (later to become HMV) in 1908.

Grainger's 'Collecting with the phonograph', Journal of the Folk Song Society, 12 (1908), 164, remains a crucial work both from a technical and historical perspective. He went on to use the instrument in ten other English counties (plus London), the vast majority of recordings being from Lincolnshire and Gloucestershire.

With the outbreak of war in 1914, Grainger and his mother moved to New York. He took up American citizenship in 1918, while serving in a US army band, and in 1921 settled in White Plains, New York, where he saw out his days.

The years 1914 to 1922 constituted the peak of Grainger's musical career. As a pianist he entered into lucrative piano-roll and gramophone recording contracts, and performed as a Steinway artist across the country with leading orchestras and conductors. His setting of a morris dance tune, Country Gardens (borrowed from Cecil Sharp's collected version at Headington Quarry, Oxford) became an instant hit on its publication in 1919. Through dozens of arrangements, it remains his best-known work.

He gave his last official American concert tour in 1948, but continued, despite worsening health from 1952, to give occasional lectures and educational concerts until he was in his late 70s. Grainger died in White Plains Hospital, New York, on 20 February 1961. He was buried alongside his mother in the West Terrace Cemetery, Adelaide, on 2 March 1961.

Most of his papers reside at the Grainger Museum, University of Melbourne, together with his was cylinder recordings. Acetate copies made under the supervision of Grainger are at the Library of Congress, Washington. Hectograph copies of his folk music transcriptions are to be found at the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library (VWML) and The British Library, London.

Percy Grainger was born George Percy Grainger at Brighton, Victoria, Australia, on 8 July 1882, the son of John Harry Grainger (1855-1917), architect and engineer, and his wife, Rosa Annie (Rose) Aldridge (1861-1922). He spent his childhood in Melbourne, Victoria, where he was privately educated under the guidance of his musically gifted mother. He received supplementary lessons in languages, art, elocution and drama, and the piano. His early interest in classical legends and Icelandic sagas influenced him for the rest of his life.

By 1895, Grainger's obvious talent with the piano led him to pursue studies in Germany. At the Hoch Conservatorium he socialised with several older British students and fell under the spell of Rudyard Kipling, settings of whose verses he worked on between 1898 and 1956. From 1901 to 1914, he made a living as a concert pianist and private teacher in London, undertaking frequent tours of northern Europe and two lengthy Antipodean visits. During the first half of his residence in London, when often fulfilling subsidiary musical roles, Grainger also depended upon sponsorship by such leading musicians as Sir Charles Villiers Stanford and Sir Henry Wood. In 1911 he changed his name to Percy Aldridge Grainger.

Like much of the English musical establishment of this period, Grainger became fascinated with folk song and set out to collect songs and tunes, initially in Lincolnshire, in 1905. Unlike most of his contemporaries, Grainger became an enthusiastic supporter of the Edison Phonograph as a means of collecting and began using it at Brigg - a small market town in North Lincolnshire, England - the following year, recording the now legendary Joseph Taylor, whom he brought to London to record songs for the Gramophone Company (later to become HMV) in 1908.

Grainger's 'Collecting with the phonograph', Journal of the Folk Song Society, 12 (1908), 164, remains a crucial work both from a technical and historical perspective. He went on to use the instrument in ten other English counties (plus London), the vast majority of recordings being from Lincolnshire and Gloucestershire.

With the outbreak of war in 1914, Grainger and his mother moved to New York. He took up American citizenship in 1918, while serving in a US army band, and in 1921 settled in White Plains, New York, where he saw out his days.

The years 1914 to 1922 constituted the peak of Grainger's musical career. As a pianist he entered into lucrative piano-roll and gramophone recording contracts, and performed as a Steinway artist across the country with leading orchestras and conductors. His setting of a morris dance tune, Country Gardens (borrowed from Cecil Sharp's collected version at Headington Quarry, Oxford) became an instant hit on its publication in 1919. Through dozens of arrangements, it remains his best-known work.

He gave his last official American concert tour in 1948, but continued, despite worsening health from 1952, to give occasional lectures and educational concerts until he was in his late 70s. Grainger died in White Plains Hospital, New York, on 20 February 1961. He was buried alongside his mother in the West Terrace Cemetery, Adelaide, on 2 March 1961.

Most of his papers reside at the Grainger Museum, University of Melbourne, together with his was cylinder recordings. Acetate copies made under the supervision of Grainger are at the Library of Congress, Washington. Hectograph copies of his folk music transcriptions are to be found at the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library (VWML) and The British Library, London.

Grainger Prophet of Modernism

In 1934 Grainger described himself to a Perth newspaper as ‘prophet of modernism’, the first to introduce Debussy and Cyril Scott to English audiences and a pioneer in performances of Ravel, Albeniz, Delius and the American composer John Alden Carpenter. Unquestionably, however, the most modern music touted in Australia immediately before the arrival of the Ballet Russes in Australia in 1936 was that by Grainger himself.

On a tour lasting the best part of two years, and in the course of hundreds of lectures, recitals and mainstream orchestral concerts, Grainger introduced to Australians the novel sights and sounds of gamelan-inspired ‘tuneful percussion’ and persistently advocated elements of primitive music—microtonality, irregular rhythm, discordance and hybridity—as the source of musical progress. On 10 January 1935 Grainger broadcast from Melbourne the world premiere of Free Music No.1 for string quartet, a work entirely composed of sliding tones.

Possibly his most radical instrumental work, its full realization would come the following year when it was transcribed for theremin and Grainger began his experiments in electronic music. This paper argues that Grainger explained and defined ultra-modernism all over Australia and to vast audiences with enormous success. While they may not have been aware of it, he had predicted several of the future paths of modern music.

On a tour lasting the best part of two years, and in the course of hundreds of lectures, recitals and mainstream orchestral concerts, Grainger introduced to Australians the novel sights and sounds of gamelan-inspired ‘tuneful percussion’ and persistently advocated elements of primitive music—microtonality, irregular rhythm, discordance and hybridity—as the source of musical progress. On 10 January 1935 Grainger broadcast from Melbourne the world premiere of Free Music No.1 for string quartet, a work entirely composed of sliding tones.

Possibly his most radical instrumental work, its full realization would come the following year when it was transcribed for theremin and Grainger began his experiments in electronic music. This paper argues that Grainger explained and defined ultra-modernism all over Australia and to vast audiences with enormous success. While they may not have been aware of it, he had predicted several of the future paths of modern music.

Grainger The All Round Man

Percy Grainger was one of the most colourful of this century's cultural figures. As a pianist and largely self-taught composer he was feted in the 1910s and 1920s, and is probably still best known for the work he 'dished up' in many different guises, Country Gardens. But Grainger aspired to the role of 'the all-round man' and nourished ideas, some brilliant, others ludicrous, across the full range of human endeavour: race, nationality, sex, language, life-style, food, clothes, technology, ecology.

The All-Round Man depicts that scrambling diversity through seventy-six uninhibited letters from Grainger's `American' years, 1914-61. These letters are fascinating to read: they are cultivated `rambles' (as Grainger actually called several of his compositions), not dissimilar to today's telephone conversations. Often written in Grainger's crunchy 'Blue-eyed English', they explore uninhibitedly every corner of his public and private life.

They reflect the magnificent attempts of a great but flawed mind to encompass the world. From the letters: `Personally I do not feel like a modern person at all. I feel quite at home in South Sea Island music, in Maori legends, in the Icelandic Sagas, in the Anglo-Saxon 'Battle of Brunnanburh', feel very close to Negroes in various countries, but hardly understand modern folk at all.'

'Music seems almost to have a "surface", a smooth surface, a grained surface, a prickly surface to the ear. All these distinguishing characteristics (roughly hinted at in the above silly similes) are to me the "body of music" are to music what "looks", skin, hair are in a person, the actual stuff and

The All-Round Man depicts that scrambling diversity through seventy-six uninhibited letters from Grainger's `American' years, 1914-61. These letters are fascinating to read: they are cultivated `rambles' (as Grainger actually called several of his compositions), not dissimilar to today's telephone conversations. Often written in Grainger's crunchy 'Blue-eyed English', they explore uninhibitedly every corner of his public and private life.

They reflect the magnificent attempts of a great but flawed mind to encompass the world. From the letters: `Personally I do not feel like a modern person at all. I feel quite at home in South Sea Island music, in Maori legends, in the Icelandic Sagas, in the Anglo-Saxon 'Battle of Brunnanburh', feel very close to Negroes in various countries, but hardly understand modern folk at all.'

'Music seems almost to have a "surface", a smooth surface, a grained surface, a prickly surface to the ear. All these distinguishing characteristics (roughly hinted at in the above silly similes) are to me the "body of music" are to music what "looks", skin, hair are in a person, the actual stuff and

Percy Grainger: A Musical Genius

The Free Music Machines of Percy Grainger.

Rainer Linz

Percy Aldridge Grainger, composer and pianist, was born in Brighton Australia in 1882 and died in White Plains NY in 1961. A highly eccentric individual with a broad range of musical and other interests, he is remembered on three continents for various aspects of his musical achievements. In Europe he is best remembered for his popular arrangements of English folk tunes such as the 'evergreen' Country Gardens . In America many people will know him as a composer and arranger of brass band music. In Australia he is remembered chiefly for his musical innovations and for what he called 'Free Music'.

Despite his populist activities, Grainger was a forward thinking musician who anticipated many innovations in twentieth century music well before they became established in the work of other composers. In his early career, like Bartok, he was an active collector and documenter of folk songs, including those of the South Pacific region. As early as 1899 he was working with so-called "beatless music", using metric successions (including such sequences as 2/4, 2½/4, 3/4, 2 ½ /4, 3/8 etc) inspired by the irregular rhythmic patterns of speech. His use of chance procedures in Random Round of 1912 predates John Cage(!), and he composed "unplayable" music onto player piano rolls while Conlon Nancarrow was still a child.

Grainger first conceived his idea of Free Music as a boy of 11 or 12. It was suggested to him by the undulating movements of the sea, and by observing the waves on Albert Park Lake in Melbourne. These experiences eventually led him to conclude that the future of music lay in freeing up rhythmic procedures and in the subtle variation of pitch, producing glissando-like movement. These ideas were to remain with him throughout his life, and he spent a great deal of his time in later years developing machines to realise his conception.

Grainger explained his concept of Free Music in a letter to critic Olin Downes in 1942:

In this music, a melody is as free to roam thru tonal space as a painter is free to draw & paint free lines, free curves, create free shapes... In FREE MUSIC the various tone-strands (melodic lines) may each have their own rhythmic pulse (or not), if they like; but one tone strand is not enslaved to the other (as in current music) by rhythmic same-beatedness.

In FREE MUSIC there are no scales - the melodic lines may glide from & to any depths & heights of (practical) tonal space, just as they may hover about any 'note' without ever alighting upon it...

In FREE MUSIC harmony will consist of free combinations (when desired) of all free intervals - not merely concordant or discordant combinations of set intervals (as in current music), but free combinations of all the intervals (but in a gliding state, not needfully in an anchored state) between present intervals...

(from: A Musical Genius from Australia Ed Teresa Balough, Perth 1982 p141)

Clearly, Free Music is conceived of as melodic (polyphonic), making use of long, sustained tones capable of continuous changes in pitch. The term glissando does not adequately describe the movement of these tones, but may give a basic idea of the type of melodic line Grainger was referring to.

A glissando is most often a performative device - it's exact shape determined in performance - and no traditional form of notation exists to adequately describe one in fine detail. Most early scores making use of glissandos describe them as a straight line between two notes of unequal pitch. Their direction of movement tends to be either up or down, much more rarely up and then down, for instance. More recent scores, especially those consisting mainly of glissandos, can be more specific.

Grainger's reference to rhythm is an interesting one, since sustained tones are not usually thought of as having rhythm. It is doubtful that he was referring to articulation or simple dynamic variation. Grainger's own scores were originally notated on graph paper, with an individual trace for both the pitch and dynamic changes of each note. If a conventional rhythm were to be notated in this way, it would mean bringing the dynamics fairly often down to zero - turning off a note in order to begin the next, and so articulate a rhythmic sequence. Yet Grainger's dynamic shapes are aligned more to the phrase than the individual note. How then is a rhythmic pulse achieved?

One answer lies in the pitch domain. The pitch undulations in a moving line serve to articulate rhythm by their change of direction or by a change in the rate of movement. Nothing in traditional music theory prepares us for this fundamental relationship between pitch and rhythm, which goes some way toward explaining why Free Music has remained misunderstood for so long, and perhaps why other composers have been slow to take up the challenge of Grainger's conception.

Harmonically, too, Free Music questions the tenets of Western musical practice by assuming a moving tone, precluding any harmonic stability. In this context, a "stable chord" is perhaps one where all parts are moving in a fixed parallel relationship to one another. Yet by definition in Western harmony, this is a "changing chord" because the fundamental is in motion. Working with this material can be a vexatious undertaking for the composer, since almost every basic assumption about musical relationships and method is called into question.

Grainger considered Free Music to be his only lasting contribution to music. Yet what remains after his death is a collection of short score fragments, a few experimental recordings, and a number of prototype machines built for the purpose of realising his ideas.

Grainger resorted to the use of machines because it was apparent that human performers on traditional instruments were not capable of producing what he required. Although some traditional acoustic instruments are able to produce "gliding tones" - instruments like the trombone and violin - they do so within comparatively narrow ranges, and the necessary control over minute fluctuations of pitch is difficult to achieve.

Nor were the available electronic instruments suitable for his purpose. Many of those developed before the 1950s tended to be keyboard-based and thus wedded to the chromatic scale. Others, such as the theremin, lacked a means of subtle and consistent control. While more complex instruments, such as the RCA synthesiser developed by Harry Olsen during the 1950s showed more promise, it was also apparent that Free Music worked against their inherent design principles; that it would be necessary to force them into something that they were simply not designed to do.

It should also be understood that Grainger's machines were not intended as performance devices. Rather, they were composing machines designed to allow Grainger to hear with his ears those sounds he heard in his head. Grainger was meticulous on this point. He insisted on hearing his compositions before allowing them to be published, and often went to extraordinary lengths to secure the means of having his more experimental work realised.

Grainger's early experiments involved modifying existing instruments, enabling them to approximate gliding tone characteristics. The "Butterfly Piano" for example, was tuned in sixth tones so that scalar passages played on it would give a closer approximation of gliding tones than a traditionally tuned piano. Grainger was not interested in microtones since his idea meant the abolition of the scale, his goal was a controlled continuous glide, and microtones were quite literally just a "step" towards this end.

A number of other experiments were carried out in collaboration with physicist Burnett Cross. Cross has described, (in a lecture given at La Trobe University in Melbourne in 1982,) connecting three electronic keyboard instruments called Solovoxes - tuned a third of a semitone apart - by means of string to a piano keyboard to achieve similar ends. This experiment, while demonstrating some feasibility, ultimately proved unsatisfactory since one of the Solovoxes invariably produced a different tone quality than the other two, and the instrument constantly played triplets!

Having decided that modifying existing instruments would not lead to satisfactory results, Grainger and Cross embarked on a project of designing and building special purpose machines. One of these, the Reed-Box Tone-Tool, might be described as a giant harmonica tuned in eighth tones.

This was a largish (table-top) instrument constructed of wood, and containing harmonium reeds. It was "played" by passing a perforated paper roll, similar to a player piano roll, across the front of the instrument and applying suction from a vacuum cleaner to the rear. While having the look and character of a home-made instrument (it is on display at the Grainger Museum in Melbourne) it nevertheless produced, according to Grainger, the first accurately specified and accurately produced gliding chords in the history of music.

Another machine, the Oscillator-Playing Tone-Tool built in 1951 , is based on a morse code practice oscillator, called a Codemaster, which was available at the time. This oscillator had a continuously variable pitch range of some three octaves, adjusted by a control on the front panel. Grainger's sketch of November 1951 shows a hand drill mounted on a Singer sewing machine, connected in such a way that the piston of the sewing machine was able to turn the handle of the drill. The shaft of the drill was fixed onto the codemaster's pitch control. In this way, turning the wheel of the sewing machine altered the pitch of the oscillator.

Rainer Linz

Percy Aldridge Grainger, composer and pianist, was born in Brighton Australia in 1882 and died in White Plains NY in 1961. A highly eccentric individual with a broad range of musical and other interests, he is remembered on three continents for various aspects of his musical achievements. In Europe he is best remembered for his popular arrangements of English folk tunes such as the 'evergreen' Country Gardens . In America many people will know him as a composer and arranger of brass band music. In Australia he is remembered chiefly for his musical innovations and for what he called 'Free Music'.

Despite his populist activities, Grainger was a forward thinking musician who anticipated many innovations in twentieth century music well before they became established in the work of other composers. In his early career, like Bartok, he was an active collector and documenter of folk songs, including those of the South Pacific region. As early as 1899 he was working with so-called "beatless music", using metric successions (including such sequences as 2/4, 2½/4, 3/4, 2 ½ /4, 3/8 etc) inspired by the irregular rhythmic patterns of speech. His use of chance procedures in Random Round of 1912 predates John Cage(!), and he composed "unplayable" music onto player piano rolls while Conlon Nancarrow was still a child.

Grainger first conceived his idea of Free Music as a boy of 11 or 12. It was suggested to him by the undulating movements of the sea, and by observing the waves on Albert Park Lake in Melbourne. These experiences eventually led him to conclude that the future of music lay in freeing up rhythmic procedures and in the subtle variation of pitch, producing glissando-like movement. These ideas were to remain with him throughout his life, and he spent a great deal of his time in later years developing machines to realise his conception.

Grainger explained his concept of Free Music in a letter to critic Olin Downes in 1942:

In this music, a melody is as free to roam thru tonal space as a painter is free to draw & paint free lines, free curves, create free shapes... In FREE MUSIC the various tone-strands (melodic lines) may each have their own rhythmic pulse (or not), if they like; but one tone strand is not enslaved to the other (as in current music) by rhythmic same-beatedness.

In FREE MUSIC there are no scales - the melodic lines may glide from & to any depths & heights of (practical) tonal space, just as they may hover about any 'note' without ever alighting upon it...

In FREE MUSIC harmony will consist of free combinations (when desired) of all free intervals - not merely concordant or discordant combinations of set intervals (as in current music), but free combinations of all the intervals (but in a gliding state, not needfully in an anchored state) between present intervals...

(from: A Musical Genius from Australia Ed Teresa Balough, Perth 1982 p141)

Clearly, Free Music is conceived of as melodic (polyphonic), making use of long, sustained tones capable of continuous changes in pitch. The term glissando does not adequately describe the movement of these tones, but may give a basic idea of the type of melodic line Grainger was referring to.

A glissando is most often a performative device - it's exact shape determined in performance - and no traditional form of notation exists to adequately describe one in fine detail. Most early scores making use of glissandos describe them as a straight line between two notes of unequal pitch. Their direction of movement tends to be either up or down, much more rarely up and then down, for instance. More recent scores, especially those consisting mainly of glissandos, can be more specific.

Grainger's reference to rhythm is an interesting one, since sustained tones are not usually thought of as having rhythm. It is doubtful that he was referring to articulation or simple dynamic variation. Grainger's own scores were originally notated on graph paper, with an individual trace for both the pitch and dynamic changes of each note. If a conventional rhythm were to be notated in this way, it would mean bringing the dynamics fairly often down to zero - turning off a note in order to begin the next, and so articulate a rhythmic sequence. Yet Grainger's dynamic shapes are aligned more to the phrase than the individual note. How then is a rhythmic pulse achieved?

One answer lies in the pitch domain. The pitch undulations in a moving line serve to articulate rhythm by their change of direction or by a change in the rate of movement. Nothing in traditional music theory prepares us for this fundamental relationship between pitch and rhythm, which goes some way toward explaining why Free Music has remained misunderstood for so long, and perhaps why other composers have been slow to take up the challenge of Grainger's conception.

Harmonically, too, Free Music questions the tenets of Western musical practice by assuming a moving tone, precluding any harmonic stability. In this context, a "stable chord" is perhaps one where all parts are moving in a fixed parallel relationship to one another. Yet by definition in Western harmony, this is a "changing chord" because the fundamental is in motion. Working with this material can be a vexatious undertaking for the composer, since almost every basic assumption about musical relationships and method is called into question.

Grainger considered Free Music to be his only lasting contribution to music. Yet what remains after his death is a collection of short score fragments, a few experimental recordings, and a number of prototype machines built for the purpose of realising his ideas.

Grainger resorted to the use of machines because it was apparent that human performers on traditional instruments were not capable of producing what he required. Although some traditional acoustic instruments are able to produce "gliding tones" - instruments like the trombone and violin - they do so within comparatively narrow ranges, and the necessary control over minute fluctuations of pitch is difficult to achieve.

Nor were the available electronic instruments suitable for his purpose. Many of those developed before the 1950s tended to be keyboard-based and thus wedded to the chromatic scale. Others, such as the theremin, lacked a means of subtle and consistent control. While more complex instruments, such as the RCA synthesiser developed by Harry Olsen during the 1950s showed more promise, it was also apparent that Free Music worked against their inherent design principles; that it would be necessary to force them into something that they were simply not designed to do.

It should also be understood that Grainger's machines were not intended as performance devices. Rather, they were composing machines designed to allow Grainger to hear with his ears those sounds he heard in his head. Grainger was meticulous on this point. He insisted on hearing his compositions before allowing them to be published, and often went to extraordinary lengths to secure the means of having his more experimental work realised.

Grainger's early experiments involved modifying existing instruments, enabling them to approximate gliding tone characteristics. The "Butterfly Piano" for example, was tuned in sixth tones so that scalar passages played on it would give a closer approximation of gliding tones than a traditionally tuned piano. Grainger was not interested in microtones since his idea meant the abolition of the scale, his goal was a controlled continuous glide, and microtones were quite literally just a "step" towards this end.

A number of other experiments were carried out in collaboration with physicist Burnett Cross. Cross has described, (in a lecture given at La Trobe University in Melbourne in 1982,) connecting three electronic keyboard instruments called Solovoxes - tuned a third of a semitone apart - by means of string to a piano keyboard to achieve similar ends. This experiment, while demonstrating some feasibility, ultimately proved unsatisfactory since one of the Solovoxes invariably produced a different tone quality than the other two, and the instrument constantly played triplets!

Having decided that modifying existing instruments would not lead to satisfactory results, Grainger and Cross embarked on a project of designing and building special purpose machines. One of these, the Reed-Box Tone-Tool, might be described as a giant harmonica tuned in eighth tones.

This was a largish (table-top) instrument constructed of wood, and containing harmonium reeds. It was "played" by passing a perforated paper roll, similar to a player piano roll, across the front of the instrument and applying suction from a vacuum cleaner to the rear. While having the look and character of a home-made instrument (it is on display at the Grainger Museum in Melbourne) it nevertheless produced, according to Grainger, the first accurately specified and accurately produced gliding chords in the history of music.

Another machine, the Oscillator-Playing Tone-Tool built in 1951 , is based on a morse code practice oscillator, called a Codemaster, which was available at the time. This oscillator had a continuously variable pitch range of some three octaves, adjusted by a control on the front panel. Grainger's sketch of November 1951 shows a hand drill mounted on a Singer sewing machine, connected in such a way that the piston of the sewing machine was able to turn the handle of the drill. The shaft of the drill was fixed onto the codemaster's pitch control. In this way, turning the wheel of the sewing machine altered the pitch of the oscillator.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)