Wednesday, June 26, 2019

Monday, June 24, 2019

Raymond Williams and Plan X

Saturday, June 22, 2019

Friday, June 14, 2019

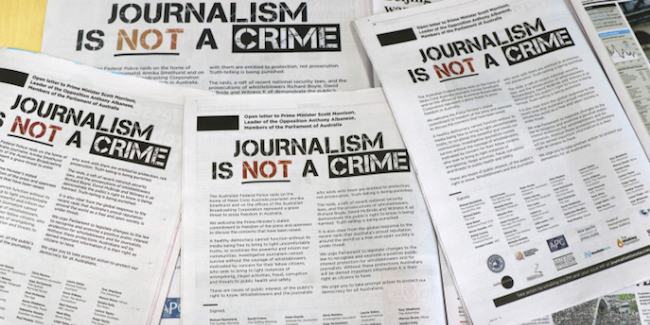

MEAA – JOURNALIASM IS NOT A CRIME

Today, MEAA, along with more than three dozen of Australia’s most prominent and acclaimed journalists and media organisations, has publicly called for urgent changes to the law to provide better protection for whistleblowers and journalists.

In an open letter published in all capital city daily newspapers today and addressed to Prime Minister Scott Morrison, Leader of the Opposition Anthony Albanese and all Members of both houses of Federal Parliament, we say prompt action is needed to protect our democracy for all Australians.

Read the letter and take action to join the call for Parliament to enshrine a positive public interest protection for whistleblowers and for journalists to protect our democracy for all Australians.

The open letter follows the raids by the Australian Federal Police last week of the home of News Corp Australia journalist Annika Smethurst and the offices of the ABC.

These raids, a raft of recent national security laws, and the prosecutions of whistleblowers Richard Boyle, David McBride and Witness K all demonstrate the public’s right to know is being harmed.

Truth-telling is being punished. Intimidation and harassment of journalists is in danger of being normalised.

It is also clear from the global response to the recent raids that Australia’s proud reputation around the world as a free and open society is under threat.

We urge Parliament to legislate changes to the law to recognise and enshrine a positive public interest protection for whistleblowers and for journalists.

Without these protections Australians will be denied important information it is their right as citizens to have.

Last week, hundreds of journalists in newsrooms around Australia stood together to say journalism is not a crime.

https://pressfreedom.org.au

Marcus Strom

Federal President

MEAA Media

Wednesday, June 12, 2019

Monday, June 03, 2019

Sunday, June 02, 2019

1873 – Defiant Women of Wychwood

Edited by Paul Jackson from an article by Wendy Pearse published in the Wychwood Local History Society Journal No 23 in 2008

In May 1873 Ascott under Wychwood shot abruptly into the national consciousness. An obscure village in West Oxfordshire suddenly featured in the major newspapers of the time (see media section) and was vehemently discussed in the Houses of Parliament. Ultimately even fervently alluded to by the fountainhead of the British Empire Queen Victoria.

But what caused this eruption? Surely not a parcel of country women, the lowly wives of farm labourers and village craftsmen. Indeed they did. Not intentionally perhaps but their actions were to resound throughout the land and in time to leave a lasting legacy on the British nation, the introduction of picketing laws and the role of local magistrates.

Just who were these women? What was their background and why should they and their actions have this stirring effect on formidable Victorian values? Today we call them the ‘Ascott Martyrs’, not perhaps as dramatic an appellation as the words imply, but there is no doubt that they were martyrs to a cause and this was their moment of glory.

Many came from families long resident in Ascott or at least their husbands did. Most were inter-related, sisters, sisters-in-law, cousins, aunts and nieces, but their inclusion in the appellation was perhaps unintentional. They may have been the ones who protested most violently but they may also have been the ones known to the constable who took their names or those slowest to disperse once he had begun this action. Exactly what did they do? Primarily they followed the simple maternal instinct of caring for their husbands and children.

Agricultural Workers Union formed

When Joseph Arch from Barford in Warwickshire began his campaign in Wellesbourne in February 1872, to improve life and conditions for the agricultural labourer, little would the villagers of Ascott have thought that in barely a year they would become a shining beacon for his movement?

In April 1872 Arch held the first meeting of what would become the Oxford District of the National Agricultural Labourers’ Union on the Green at Milton (the adjacent village to Ascott) and fifty men joined there and then. By the end of May over 500 men in the area, divided amongst 13 branches, had become members and amongst that number must have been labourers from Ascott.

The following April the agricultural labourers working for Robert Hambidge at Crown Farm in the middle of the village, unable to feed, clothe and support their families on their minimal wage of 10s a week, asked for an increase to 14s. (Hambidge offered 13s? Ed) and gave a week’s notice to strike. This was official procedure arising from the Liberal Government Act of 1871 making Unions and their activities legal except for the action of preventing anyone else from working. Of course this tied the strikers’ hands but perhaps someone in Ascott realised that it did not tie the hands of their wives and daughters who were not members of the Union.

Farmer decides to break strike

After a couple of weeks without labour Robert Hambidge decided on action. He hired two teenagers, John Hodgkins and John Millin from Ramsden (a nearby village) and on the 12th of May went off to Stow Fair leaving these lads with instructions to begin hoeing a certain field. It is believed to have been one of those near to the Leafield turn on the Charlbury to Burford Road. As the lads neared the field gate they found awaiting them a crowd of about 40 women and girls. Whether this was a planned action or spontaneous we do not know. It was suggested that some women sported sticks and used them to intimidate the lads but subsequently no proof of this could be produced, and the accepted scenario is that amongst jostling, joviality and suggestions the lads greatest threat came with the impromptu call to remove their trousers! Abashed the boys sought support and either they or Robert Hambidge’s wife enlisted the aid of the local constable. The women who imagined that they had won the boys over to their side of the argument, were amazed but before they could disperse, seventeen of their names had been noted by the constable.

Woman charged

Upon his return from Stow Robert Hambidge was incensed and demanded justice. The women must be brought before the magistrates. This took place on May 21st at the newly built Police Station in Chipping Norton where the women were charged with intimidation under the Criminal Law Amendment Act. The two magistrates who tried the case were the Rev. Thomas Harris of Swerford and the Rev. William Carter of Sarsden, the son in law of Lord Langston of Sarsden Estate. Rev. Carter had already spent the years 1852-1868 as the Vicar of Shipton and may have had prior knowledge of the villagers of Ascott. Six of the women were Baptists and one was a Methodist and their persuasion may well have further antagonised the Church of England J.P.s at a time when the swelling growth of non-conformists was a ripening source of irritation to the established church.

In Court

The women had no legal representation at the court and this on the surface might seem remiss on the part of Joseph Arch but perhaps he took the view that should the women be convicted and a harsh sentence imposed publicity for the Union would be excellent. (Apparently the Union had come prepared to pay the fines Ed) There should really have been no case to answer. A few months before a similar case in nearby Woodstock had resulted in the men involved being bound over to keep the peace. This trial rested simply on the word of two teenage lads against that of 17 women whose honesty had never before been questioned. But Hambidge demanded justice, pressured Magistrate Harris into pronouncing the severest sentence possible under the law and although Carter was reluctant and agonised over the decision before finally concurring with his colleague, one woman was acquitted whilst nine more were sentenced to seven days in gaol and the other seven to ten days. To add insult to injury the sentence was to be served with hard labour.

Local reaction

The news spread like wildfire and in no time a mob of 2000 locals surrounded the police station where the women, two with young babies, awaited transport to the Oxford Gaol. Ugly scenes ensued, tiles were smashed, windows broken, but the strength of the new building proved its worth and although incidents occurred until late in the evening, by midnight the crowd had dispersed. In the early hours of the morning the support urgently summoned by Police Superintendent Lakin and the Mayor (as they could not get to the railway station Ed), finally turned up in the form of constables and a large wagon into which the women were rapidly bundled without even time to adequately clothe the babies against the coldness of the night.

Oxford Gaol

They arrived at Oxford Gaol at 6 o’clock in the morning, cold, questioning and probably terrified, but defiant. Hard labour consisted of washing and ironing, jobs to which they were well accustomed, but the two with babies were excused these chores and some milk was found for the infants. However for these women who probably in the whole of their lives had hardly left homes, families and familiar territory, the ordeal must have been heartrending. In Ascott over a dozen children under ten were suddenly deprived of their mothers. The women may have been sustained by the pride they felt in making a stand for an improvement in their life and living but those prison days must have seemed endless as their concern grew for their families back home.

National reaction

Whilst the women served their sentence matters did not stand still. Grumbles about the events grew by the hour, the national newspapers took up their cause, debates were held in Parliament and the Home Secretary corresponded with the Duke of Marlborough who heartily endorsed the clergymen’s action. Such behaviour by the lower class was beyond understanding and could not be condoned by the middle and upper classes. The news reached the ears of Queen Victoria whose unhappiness with her Liberal Government may well have prompted her feelings against the proceedings and she demanded that their hard labour must be rescinded and the women given a free and complete pardon.

Release

Unfortunately by the time all these procedures had occurred ten days had passed and the last seven women were released. But with such celebrations. Joseph Arch and the Union officials milked the occasion for all it was worth. 150 people thronged the prison gates as the women emerged, a hearty breakfast had been arranged before they were conveyed in style to the Kings Arms in Woodstock for a sit down lunch. Whilst they were incarcerated, the women were probably little aware of the widening controversy ensuing from their actions, so they must have been quite overwhelmed by their reception. Mr Holloway, the Secretary of the Union instructed the wagon to drive through Blenheim Park effectively thumbing their noses at the Duke of Marlborough, before continuing on to Chipping Norton where a large crowd including the women’s families awaited them.

In Ascott outside Crown Farm, the women were presented with £5 (10 weeks wages) each by Joseph Arch. This money had come in donations from the general public. They also each received a silk dress in Union blue or more likely the material with which to make a dress. The Queen is believed to have sent them all a red flannel petticoat and 5s in cash, a half week’s wages.

Follow up

The women’s ordeal was over but how much greater publicity could the Union have wished for? Already the newspapers were labelling them ‘Martyrs’ to what was believed to be a very just cause.

They were just ordinary women, the majority of them the wives of agricultural labourers. Ascott was and always had been an agricultural village. No resident lord of the manor, the majority of the village and land was owned by Lord Churchill of Cornbury and Wychwood, a relative of the Duke of Marlborough. Approximately 460 souls lived in the village including a number of farmers and their families, mostly tenants of Lord Churchill, Brasenose College or the daughter of the late vicar of Iffley.

In December 1928 eleven years before her death Fanny Honeybone was interviewed by a reporter from ‘The Land Worker’ (see media section) and contributed her memories of those stirring times and the pride she felt to be ‘left as the one survivor of the sixteen women who suffered the penalty of the law for the cause of the agricultural labourers. She said that “there was something of the idea of fun in what we did – certainly no intention to harm them”.

Legacy

But what was their legacy? Primarily their actions led to a change in the law which resulted in the right to peaceful picketing. Over the next few years the use of local members of the clergy as J.P.s gradually disappeared. And in time the Union did help farm labourers to achieve a rise in their wages. But unfortunately this came about at the same time as a deep depression in both climate and conditions severely shook British Agriculture, a situation which scarcely improved until everything changed with the onset of the First World War.

Today the memory of these ordinary but defiant women lives on, recorded on seats around a commemorative tree planted in 1973 on the village green at Ascott.

Saturday, June 01, 2019

New Zealand and Australia's Eight Hour Day

With banners flying over floats representing their various trades, Dunedin unionists parade through the Octagon on New Zealand's first official Labour Day, in 1890. The annual parade began as an occasion to demonstrate the strength and aims of the union movement.Courtesy of Alexander

With banners flying over floats representing their various trades, Dunedin unionists parade through the Octagon on New Zealand's first official Labour Day, in 1890. The annual parade began as an occasion to demonstrate the strength and aims of the union movement.

Labour Day's origins are tied to Australian shipping companies but employment issues quickly travelled across the Tasman, resulting an a 10-week strike and an annual holiday, reports Jessica Long.

Industrial action paralysed the whole trans-Tasman shipping trade for 10 weeks from August 27, 1890.

After the strike ended, Labour Day was celebrated for the first time on October 28 by union members and supporters in New Zealand, as a show of strength in the aims of the movement.

Unionists also celebrated the Maritime Council's establishment and the 50 years since Samuel Parnell, a carpenter and the council's founder, won an eight-hour work day.

The 1890 strikes all started when a stoker, who was a prominent unionist, was fired. Friction between employer and employee ensued but trouble really began when ship owners refused to affiliate the Officers' Association with Australia's Trades and Labor Council in New South Wales and Victoria.

The officers sought the tie-up to distinguish them "from ordinary servants" when they were at sea, but their companies refused to comply with demands.

A strike under the Australian Maritime Union ensued in Australia, filtering down to include some workmen. Ship owners in New Zealand started to worry the tide would drift across the Tasman.

But New Zealand's Maritime Council, an umbrella organisation of transport and mining unions founded on October 28, 1889, initially wanted to avoid a strike.

However, tensions between Kiwi ship owners and their workers worsened when an attempt was made to bring all organised labour into one big federation.

Wharf labourers in Sydney refused to work New Zealand's Waihora. A few days later more ships arrived and free labour was brought in to work them. It was the turning point – a general strike was imminent.

Feelings were felt deepest in Wellington and when word arrived that free labour was used, there were "incipient riots and conflicts".

Samuel Duncan Parnell, who initiated the eight hour working day. Taken by Henry Wright in June 1890

"The feeling of many years found vent in the strike ... There had been sweating in the factories and retaliatory measures against unreasonable employers, and all the bitterness and uncharitableness came to the surface," the Feilding Star reported.

"The Maritime Council in New Zealand called out all its men from the Union Company's vessels. The business of the country consequently came to a standstill, and the train services were considerably curtailed."

An estimated 4000 unionists stopped work for 10 weeks, which cost the country an estimated £200,000 (about $39,728,607.59, according to the Reserve Bank of New Zealand inflation calculator).

The result "seriously disturbed industry and embarrassed financial operations", the Marlborough Express reported on November 25, 1913 – when New Zealand was in the throes of yet another series of industrial strikes.

The 1890 strike involved "a series of violent quarrels between employers and employed", and become the first major nationwide labour dispute in New Zealand, according to the New Zealand History website.

It was drawn out and heated but it all came to an end when industries began to be worked without the strikers. It basically came down to a conference where Sir George McLean, a Union Company representative and Otago MP, "would listen to nothing but unconditional surrender" the Feilding Star said.

Labour Day commemorates the struggle for an eight-hour working day. New Zealand workers were among the first in the world to claim this right when, in 1840, the carpenter Samuel Parnell won an eight-hour day in Wellington.

Labour Day commemorates the struggle for an eight-hour working day. New Zealand workers were among the first in the world to claim this right when, in 1840, the carpenter Samuel Parnell won an eight-hour day in Wellington. "This the workers' representatives had to accept, and so the strike ended."

Some employers then refused to recognise unions, blacklisted their members, slashed wages and ignored perilous conditions.

The strike was deemed a "failure" and when the Liberal Government took office in 1891 it formed the Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act.

New Zealand then became the first in the world to outlaw strikes and introduce compulsory arbitration as a move to make unions a political ally. The system stuck until 1973.

Gisborne parade in 1908. Floats represented different trades, and banners carried union slogans, like 'unity is strength'. Courtesy of Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries,

New Zealand workers were among the first in the world to claim the right to an eight-hour working day.

On October 28, 1890, an elderly Samuel Parnell appeared at the first Labour Day event in Wellington as parades were trotted out elsewhere in the country, boasting thousands of supporters who saw the day as a movement to improve employment conditions for all workers.

Even government employees were given the day off to attend the parades and in 1899 Parliament legislated to make Labour Day a national, public holiday.

The statutory public holiday, on the second Wednesday in October, was celebrated by everyone for the first time in 1900.

With banners flying over floats representing their various trades, Dunedin unionists parade through the Octagon on New Zealand's first official Labour Day, in 1890. The annual parade began as an occasion to demonstrate the strength and aims of the union movement.

Labour Day's origins are tied to Australian shipping companies but employment issues quickly travelled across the Tasman, resulting an a 10-week strike and an annual holiday, reports Jessica Long.

Industrial action paralysed the whole trans-Tasman shipping trade for 10 weeks from August 27, 1890.

After the strike ended, Labour Day was celebrated for the first time on October 28 by union members and supporters in New Zealand, as a show of strength in the aims of the movement.

Unionists also celebrated the Maritime Council's establishment and the 50 years since Samuel Parnell, a carpenter and the council's founder, won an eight-hour work day.

The 1890 strikes all started when a stoker, who was a prominent unionist, was fired. Friction between employer and employee ensued but trouble really began when ship owners refused to affiliate the Officers' Association with Australia's Trades and Labor Council in New South Wales and Victoria.

The officers sought the tie-up to distinguish them "from ordinary servants" when they were at sea, but their companies refused to comply with demands.

A strike under the Australian Maritime Union ensued in Australia, filtering down to include some workmen. Ship owners in New Zealand started to worry the tide would drift across the Tasman.

But New Zealand's Maritime Council, an umbrella organisation of transport and mining unions founded on October 28, 1889, initially wanted to avoid a strike.

However, tensions between Kiwi ship owners and their workers worsened when an attempt was made to bring all organised labour into one big federation.

Wharf labourers in Sydney refused to work New Zealand's Waihora. A few days later more ships arrived and free labour was brought in to work them. It was the turning point – a general strike was imminent.

Feelings were felt deepest in Wellington and when word arrived that free labour was used, there were "incipient riots and conflicts".

Samuel Duncan Parnell, who initiated the eight hour working day. Taken by Henry Wright in June 1890

"The feeling of many years found vent in the strike ... There had been sweating in the factories and retaliatory measures against unreasonable employers, and all the bitterness and uncharitableness came to the surface," the Feilding Star reported.

"The Maritime Council in New Zealand called out all its men from the Union Company's vessels. The business of the country consequently came to a standstill, and the train services were considerably curtailed."

An estimated 4000 unionists stopped work for 10 weeks, which cost the country an estimated £200,000 (about $39,728,607.59, according to the Reserve Bank of New Zealand inflation calculator).

The result "seriously disturbed industry and embarrassed financial operations", the Marlborough Express reported on November 25, 1913 – when New Zealand was in the throes of yet another series of industrial strikes.

The 1890 strike involved "a series of violent quarrels between employers and employed", and become the first major nationwide labour dispute in New Zealand, according to the New Zealand History website.

It was drawn out and heated but it all came to an end when industries began to be worked without the strikers. It basically came down to a conference where Sir George McLean, a Union Company representative and Otago MP, "would listen to nothing but unconditional surrender" the Feilding Star said.

Labour Day commemorates the struggle for an eight-hour working day. New Zealand workers were among the first in the world to claim this right when, in 1840, the carpenter Samuel Parnell won an eight-hour day in Wellington.

Labour Day commemorates the struggle for an eight-hour working day. New Zealand workers were among the first in the world to claim this right when, in 1840, the carpenter Samuel Parnell won an eight-hour day in Wellington. "This the workers' representatives had to accept, and so the strike ended."

Some employers then refused to recognise unions, blacklisted their members, slashed wages and ignored perilous conditions.

The strike was deemed a "failure" and when the Liberal Government took office in 1891 it formed the Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act.

New Zealand then became the first in the world to outlaw strikes and introduce compulsory arbitration as a move to make unions a political ally. The system stuck until 1973.

Gisborne parade in 1908. Floats represented different trades, and banners carried union slogans, like 'unity is strength'. Courtesy of Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries,

New Zealand workers were among the first in the world to claim the right to an eight-hour working day.

On October 28, 1890, an elderly Samuel Parnell appeared at the first Labour Day event in Wellington as parades were trotted out elsewhere in the country, boasting thousands of supporters who saw the day as a movement to improve employment conditions for all workers.

Even government employees were given the day off to attend the parades and in 1899 Parliament legislated to make Labour Day a national, public holiday.

The statutory public holiday, on the second Wednesday in October, was celebrated by everyone for the first time in 1900.

|

| Nuclear Free Postage Stamp 2008 |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)