The forgotten voices of Lancashire’s poverty-stricken cotton workers during the US civil war have been heard for the first time in 150 years, after researchers at the University of Exeter unearthed a treasure trove of poetry.

Up to 400,000 of the county’s cotton workers were left unemployed when the war stopped cotton from reaching England’s north-west in the 1860s and the mills were closed. Without work, they struggled to put food on the table, and experts from the University of Exeter have discovered that many of them turned to poetry to describe the impact of the cotton famine.

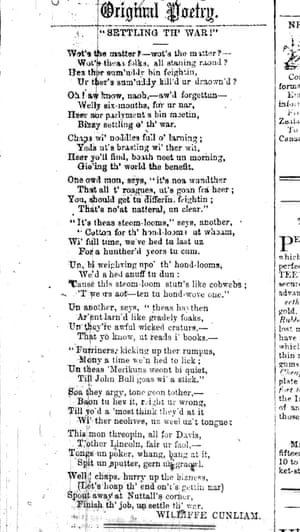

Written between 1861 and 1865, many of the poems are by the workers most affected by the famine. Around a quarter of the 300 poems discovered so far are written in the Lancashire dialect, with some published in local newspapers or simply sent in letters. All the poems were held in local archives and had never been studied or collected.

Simon Rennie, who is leading the project, said: “A lot of these poems are anonymous, or signed with initials; some of the writers describe themselves as ‘a boatbuilder’, ‘a millworker’, or ‘an operative’ … What we’ve found here is a significantly different view of a period of history that is already well documented – it’s that sense of history from below.

“It shows how strong working-class poetic culture was at the time – if you’re working for 12 hours, you might still have time to write a poem in the evening,” he added.

The poems describe the grinding misery of poverty. In A Song of the Cotton Famine, the anonymous author asks: “Shall I again permitted be / To send my kids to schoo’, / Where they con larn to read and write, / Do sums by figures too?” In A Mother’s Wail, by John Plummer in the voice of a woman mourning her dead daughter, he writes of how: “She was starved to death, I say, / Because of the fierce and cruel strife / ’Mid our kinsmen far away.”

Rennie pointed to one poet in particular: the wool sorter Williffe Cunliam, who wrote six of the poems uncovered to date. “I think he was a very good poet – a great poet,” said Rennie. “We don’t have enough of his work to say he was a literary star, but he was fantastic; we’ve found very high-quality work.” Cunliam – whose real name was William Cunliffe - writes in both dialect and standard English, appealing for help for the poor in one poem – “Ye rich and high, / With lands and mansions fine, / Think of the poor in their cold, bare homes, / Can you let them starve and pine?” – while in others, his tone remains dry and ironic.

Only a few of the poems were written by women. “They tend to be middle-class women writing to garner support for charitable causes,” said Rennie. “There is quite a bit of representation of working-class women [in the poems], but we have yet to find a poem that is verifiably by one of them.”

The researchers expect to find hundreds more poems, as the newspapers of the day would generally have a daily poetry column. Rennie said the sheer range shows “there was a vibrant literary culture among Lancashire cotton workers”.

“These poems have an extraordinary range and emotional intensity. Some are in heavy dialect, some are comic, some have high literary ambition and others are satirical. We see repetition of the same types of characters, phrases and poetic rhythms,” he said. “They reveal a previously unheard commentary on one of the most devastating economic disasters to occur in Victorian Britain.”

Rennie and his team have created a publicly accessible database of the poems, along with 100 recordings of them being read. “We are trying simply to show they can be heard as well as read,” said Rennie’s colleague Ruth Mather. “The Lancashire dialect pieces in particular are fiendishly difficult to recite, and we are aware that pronunciation of many terms may be contentious. But we hope we are bringing alive an important part of Lancashire cultural history that has lain relatively dormant for more than 150 years.”

No comments:

Post a Comment